Who distorts customs statistics between Kazakhstan and China

Last year saw a growing discrepancy between Kazakhstan’s import data (from China) and China’s export data (to Kazakhstan). The Supreme Audit Chamber of Kazakhstan (SAC) highlighted this trend in its statement regarding the government’s implementation of the budget for 2023. Kursiv Research reviewed the SAC’s statement and official statistics to understand why these discrepancies have increased, despite President Tokayev’s instruction to bring order to the Kazakhstan-China border, as voiced in his state-of-the-nation address following the events of January 2022.

State auditors believe the growing mismatch in mirror statistics indicates ineffective customs administration for certain commodity groups. A poor customs administration, in turn, reduces the collectability of taxes and other budgetary payments. Last year, the state budget fell short by approximately $2.9 billion of the estimated $29.6 billion in tax revenues.

The significant discrepancy between Kazakhstan’s and China’s data causes economic damage and the issue also has political dimensions. A few days after the January events, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev addressed the lessons drawn from the tragedy. He instructed the Prosecutor General’s Office, the Ministry of Finance and the Financial Monitoring Agency to tackle issues at the Kazakh-Chinese border where, as he put it, «cars are not inspected; taxes and duties are not paid. The disparity between the mirror statistics with Chinese customs bodies reaches billions of dollars.»

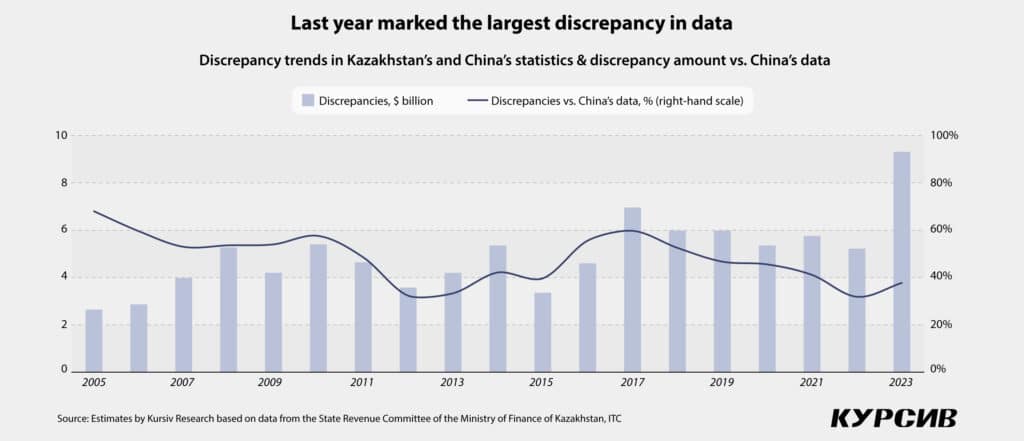

The first year following the presidential instruction saw a decrease in the discrepancy. It fell from $5.7 billion in 2021 to $5.2 billion in 2022. This progress was evident from the discrepancy amount versus China’s data, which reflects the overall trade turnover trend. This indicator decreased from 41.1% to a 20-year low of 31.9%.

However, shortly after this, conditions at the Kazakhstan-China border saw a return to their previous state. By the end of 2023, the discrepancy had increased to $9.3 billion, marking the highest discrepancy in absolute terms over the last 20 years. The deterioration in customs administration is also reflected in the rise of the discrepancy indicator to 37.7% (discrepancy amount vs. China’s data).

The SAC has identified this negative trend. In its statement on the implementation of the state budget for 2023, the auditors highlighted several points, some of which Kursiv Research has reproduced in this article.

It’s important to note that the SAC’s statement, published in June this year, was based on preliminary data. The State Revenue Committee of the Ministry of Finance (SRC) typically updates its statistics in August, replacing preliminary data on its website with final figures. As a result, estimates by Kursiv Research may slightly differ from the SAC’s figures but remain consistent with the state auditors’ interpretations.

Differing estimates

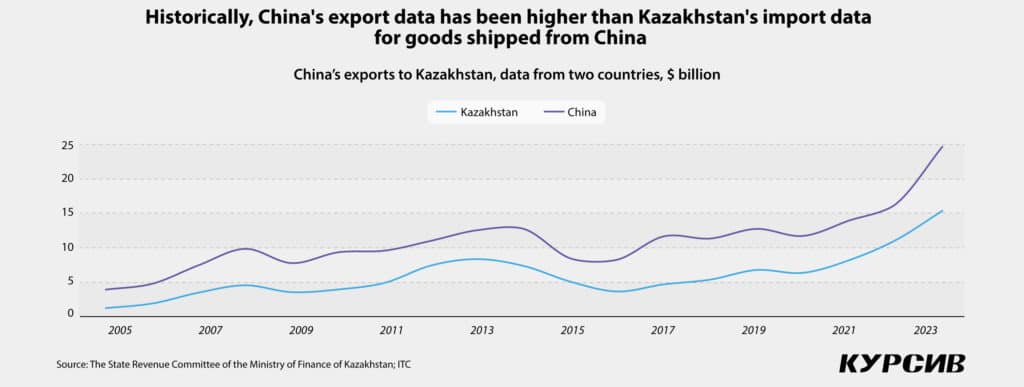

Kazakhstan imported $15.4 billion in goods from China last year, according to the SRC. In contrast, the International Trade Centre (ITC) reports that China’s customs authorities recorded commodity exports to Kazakhstan totaling $24.7 billion. This results in a $9.3 billion discrepancy. The discrepancy as a percentage of China’s reported exports to Kazakhstan has increased to 37.7%, up from 31.9% at the end of 2022.

A few clarifications are necessary. In March 2024, Yeldos Saudabayev, then director of the customs control department at the SRC, indicated that in 2023, the relative discrepancy remained at the same level as the previous year (32.7%). He attributed this to enhanced administration and process automation. This ratio, however, appears to have been based on preliminary statistics, which showed Kazakhstan imported $16.8 billion from China. Furthermore, the 32.7% ratio was within the target benchmark set by the Ministry of Finance’s development plan for 2023-2027, which aimed to keep the discrepancy with Chinese customs statistics below 37% by the end of last year.

However, SAC experts supplemented calculations based on preliminary customs statistics with data obtained during the audit, where tax reporting was compared with customs declarations. An excerpt from the SAC statement reads:

«The audit revealed that by manipulating the customs value of goods imported from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) — specifically, for groups such as the 61st (‘Articles of apparel and clothing accessories, knitted or crocheted’), the 62nd (‘Articles of apparel and clothing accessories, not knitted or crocheted’), the 64th (‘Footwear, gaiters and the like; parts of such articles’) and other goods — external trade actors (ETA), as authorized economic operators (AEO), overestimated the value of these imports to Kazakhstan from the PRC by $1.4 billion. This manipulation occurred when placing goods under the customs warehouse procedure (which does not require paying customs duties and taxes and inspecting customs value) before placing them under customs procedures for release for domestic consumption (Import-40).»

As a result, the state auditors established that the actual amount of discrepancies was around $9.3 billion, which aligns with the final statistics of Kazakhstani customs.

A little too much?

What is the economic rationale behind the $9.3 billion discrepancy or the 37.7% difference in mirror statistics compared to China’s customs data? First, the mirror statistics method isn’t always the most accurate, as data can diverge even when no laws are broken. Several factors contribute to this, namely: some countries include operations in free economic zones in their foreign trade statistics, while others don’t; there is often a time lag between the shipment and receipt of goods; inaccurate declaration of goods at import; some countries account for re-exports, re-imports or international transit differently, despite the UN’s recommendation that imports be defined by the country of origin, exports by the last country of destination and transit data excluded from foreign trade statistics. Additionally, imports may be recorded at cost, insurance and freight (CIF) prices, while exports are recorded at free-on-board (FOB) prices, leading to discrepancies due to differences in insurance and logistics terms.

Second, considering these factors, discrepancies exceeding 50% in mirror statistics studies should be viewed with caution. Such discrepancies occur across many countries and should not be automatically interpreted as evidence of high corruption risks in customs.

In February 2022, shortly after the president’s address, Yerulan Zhamaubayev, then minister of finance, explained the $5.7 billion discrepancy in mirror statistics with China’s data at the end of 2021. According to Zhamaubayev, about $300 million (just over 5% of the $5.7 billion) was due to methodological issues. Approximately $2.6 billion (46%) was related to the transit of Chinese goods through Kazakhstan. The largest share, $2.8 billion (49%), was attributed to false declarations. Based on this $2.8 billion in inaccurate declarations, Zhamaubayev estimated that the state budget lost over $311 million.

So, given the above, the 37.7% discrepancy in mirror statistics compared to China’s data reveals little, as it represents a condensed value for all groups of goods, obtained by summing up both positive and negative discrepancies.

In this context, a negative discrepancy occurs when the statistics from a trading partner (China) exceed those from Kazakhstan. In other words, this suggests that the customs value of the goods is understated. But when do participants in foreign trade typically understate the customs value?

Globally, understating customs value is a common practice because the lower the declared value, the less the declarant has to pay in taxes and fees for moving goods across the border. The customs value is initially declared by the declarant (or a customs representative acting on behalf of the cargo owner) and its accuracy is verified by customs authorities. Sometimes, an independent company is also involved in assessing the value.

There are also instances when an external trade actor might overstate the customs value. This usually occurs when the rate of customs duties and other payments for moving goods across the border is significantly higher than the taxes that the economic agent must pay after reselling the goods. In such cases, by overstating the customs value, the agent pays a larger amount to the budget upfront, then sells the goods either with a minimal markup or at a loss — at least on paper — since the price declared at the border was incorrect. This understated revenue or declared loss allows the agent to «optimize» taxes, such as the profit tax. That’s how a positive discrepancy occurs.

Apparel, footwear and toys

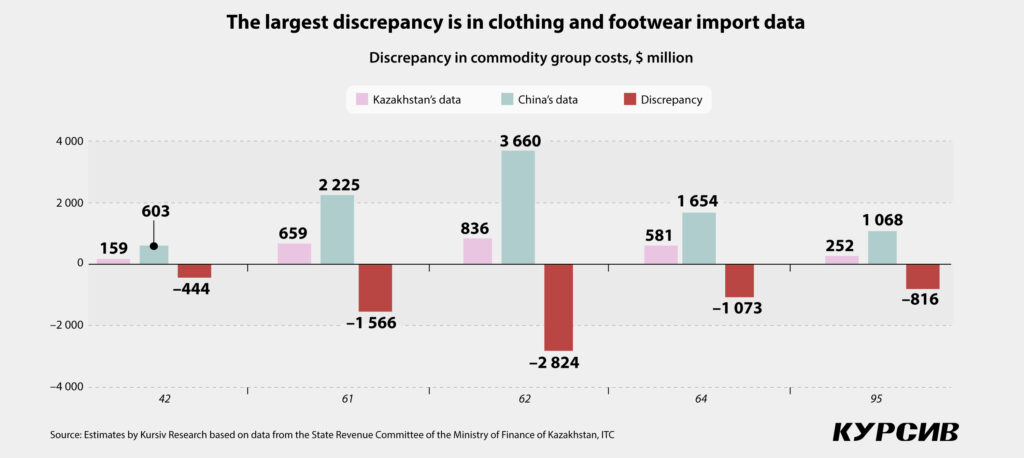

Traditionally, the largest volume of discrepancies in imports from China comes from commodity flows with a negative difference. A breakdown of the condensed value by two-digit codes of the Commodity Nomenclature of Foreign Economic Activity (CN FEA) reveals that in 2023, the top five groups with the most significant negative discrepancies are consistent with those from previous years.

Commodity group 62 stands out, with discrepancies reaching -$2.8 billion or 77% compared to Chinese customs data. Kazakhstan’s data for commodity group 61 was nearly $1.6 billion lower than China’s (a 70% discrepancy). For commodity group 64, the negative difference was approximately $1.1 billion (65%).

In group 95 (‘Toys, games, and sports requisites; parts and accessories thereof’), the negative discrepancy grew to $816 million (76%). The top five is rounded out by commodity group 42 (‘Articles of leather; saddlery and harness; travel goods, handbags and similar containers; articles of animal gut (other than silkworm gut)’), which had a negative difference of $444.4 million (74%).

For these five groups, the total amount of discrepancies was about -$6.7 billion, representing 72.2% of the overall discrepancies. It should be noted that the SAC statement shows slightly different figures, but the top groups with the largest negative discrepancies remain the same and in the same order.

One reason for the significant irregularities may be the large volume of counterfeit and smuggled goods passing through the Kazakhstan-China border. Almost all of the goods mentioned above are easier to counterfeit due to their physical properties compared to items like gadgets. Unlike bulky goods, these items are easier to hide from customs officers. Additionally, unlike means of production, where quality is checked by customers with the necessary expertise, buyers often cannot evaluate consumer goods as they lack specialized knowledge.

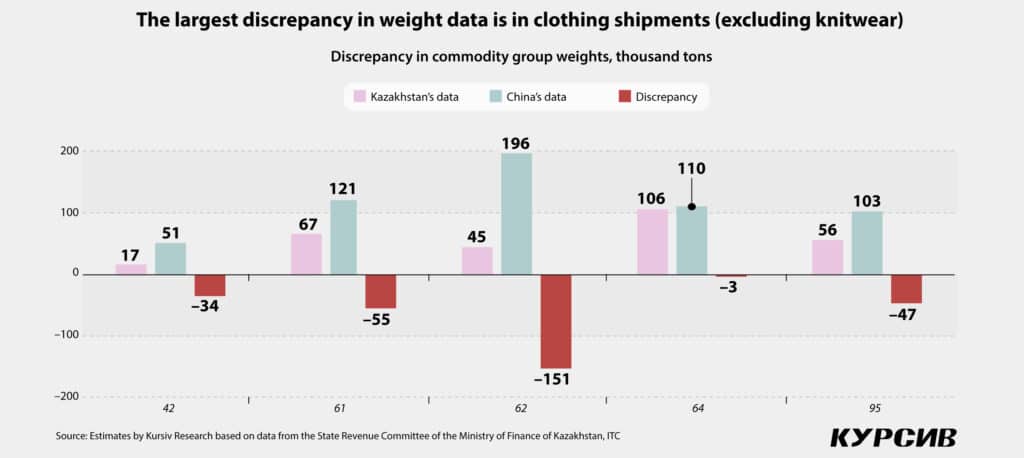

The flow of counterfeit and smuggled goods can be indirectly indicated by a weight discrepancy exceeding 50% compared to China’s data. According to our calculations, a critical discrepancy was recorded for commodity groups 62 (4.4 times) and 42 (3 times). The absence of a crucial discrepancy in the other three groups suggests manipulation of customs value.

Reliable operators

In their statement, state auditors highlight an interesting point: «In the volume of imports of the above groups of goods from China [the five commodity groups mentioned earlier], about half are accounted for by authorized economic operators (AEOs).»

So, what is an AEO? According to the Customs Code of the EAEU, an AEO is an enterprise registered within the Union and included in a special register. Companies with this status enjoy a simplified procedure for cargo clearance when crossing the borders of EAEU states. The SRC website explains:

«The privileges applied to customs operations and checks depend on the type of AEO certificate. When using special customs simplifications, time and financial costs for passing through customs are minimized and the logistics chain is optimized. Customs officers trust a person with AEO status, which is especially important when a legal entity operates in Russia, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.»

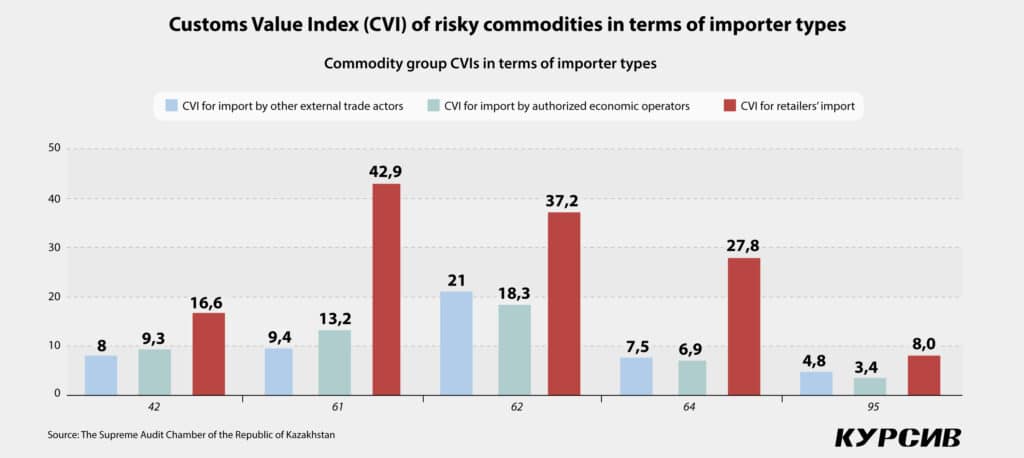

The state auditors compared the customs value index (CVI), a statistical benchmark that reflects the ratio of the value of goods to their weight, for importers under different customs regimes. According to the SAC’s statement, «The CVI for these imported goods by AEOs enjoying ‘most-favored-nation’ treatment is lower than the CVI for other categories for commodity groups 62, 64 and 95. Additionally, it is lower than the CVI of official retailers for all high-risk commodity groups.» In simpler terms, AEOs import significantly more goods for the same amount of money compared to other external trade actors.

«These findings highlight the ineffectiveness of customs administration measures concerning AEOs,» the SAC experts concluded.

What’s the cost?

State auditors analyzed imports from China at the six-digit CN FEA level, identifying 3,808 sub-items with significant positive and negative discrepancies.

In 2023, they found 2,063 sub-items with a significant positive variance (China’s data exceeding Kazakhstan’s), totaling almost $5.8 billion and 1,745 sub-items with a negative variance (Kazakhstan’s data exceeding China’s), totaling -$13.7 billion.

To estimate economic losses, the auditors used the import duty exemption rate for positive discrepancies and the VAT exemption rate for negative discrepancies. They calculated that estimated economic losses in customs duties and VAT amounted to just over $1 billion, based on last year’s average exchange rate.

This shortfall represents about one-third of the tax revenue deficit that nearly triggered a budget crisis last year, which the government narrowly avoided by tapping into the National Fund.