Kazakhstan’s secretive mega-projects: Why government is silent

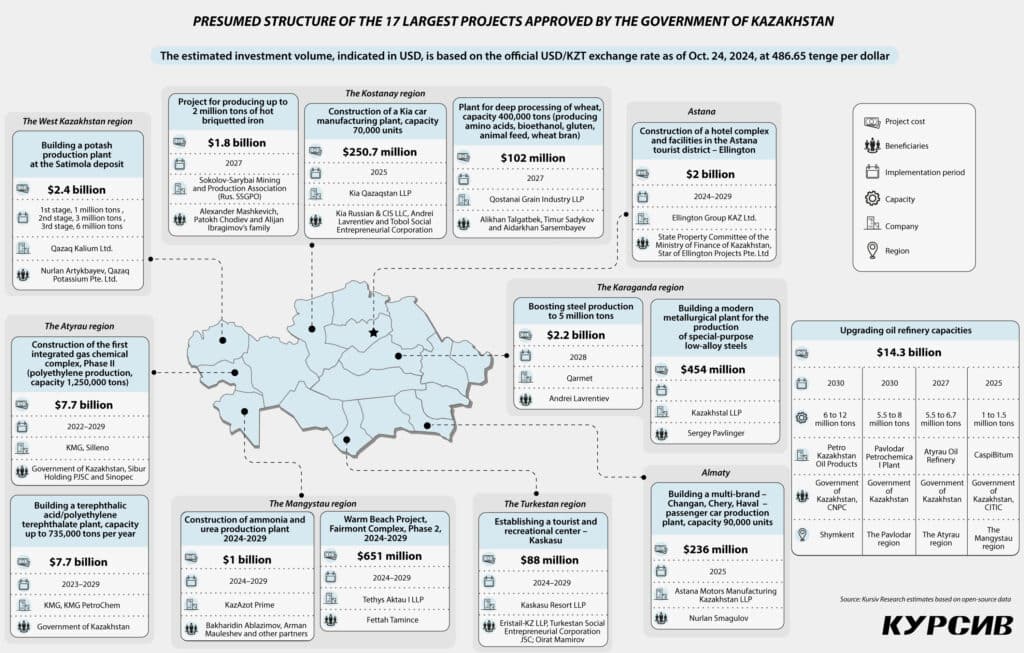

After publicly announcing the approval of 17 large projects with a total investment of $30 billion, Kazakhstan’s government has been slow to reveal the specifics. Kursiv Research has identified projects that align with the descriptions previously provided by authorities, named the beneficiaries and analyzed the differences between the industrial policies of the «Old» and «New» Kazakhstan.

A confidential list

Devising a list of 17 megaprojects — let’s call it the Top 17 — is part of the government’s efforts to implement the president’s directive, as detailed in a statement on the official website of the prime minister of Kazakhstan in late August. The announcement noted that «the government approved a list of 17 major projects with an investment volume of more than KZT15 trillion [nearly $30 billion].»

While the official source did not specify the project names, it did reveal some details about the types of capacities being developed. Based on the descriptions of the intended products, the projects appear to focus on sectors like metallurgy, petrochemicals, chemicals, food raw material production and the tourism and hospitality industries.

«Implementing these projects will create more than 26,000 new jobs, increase exports by KZT6 trillion [$12 billion] and provide import substitution valued at over KZT1.5 trillion [$3 billion]. These initiatives also support the development of high-tech industries, enhance local workforce skills and establish offtake agreements with domestic manufacturers,» the government stated.

According to the Ministry of Industry and Construction, the Ministry of National Economy (MNE) was responsible for compiling the list of these projects, while the Ministry of Industry only proposed a few. However, the MNE declined to share the list, claiming that it is «currently under revision to account for market development priorities and economic sector conditions,» and to address «counter-obligation issues with investors.»

The ministry was unable to specify which legal act had been used to approve the project list. In its response, the MNE stated that, together with other government agencies, it had identified «17 major projects aimed at creating high value-added clusters.»

No secrecy there

The team at Kursiv Research compared information from the official announcement with public statements by officials, data from the industrialization map, state programs, the Development Bank of Kazakhstan’s (DBK) list of projects under implementation or consideration and other open-source data. Based on this analysis, we identified a group of 17 projects that best match the description of the Top 17. Publicly available information on the production capacities of 10 of these projects aligns with data mentioned in the government’s announcement. Total investment in the Top 17 is estimated at $33 billion, based on the current USD/KZT exchange rate.

The largest projects are in the petrochemical sector, including the modernization of KazMunayGas’s (KMG) four oil refineries, planned by 2030 at a total cost of $14.3 billion. The government’s description closely matches the modernization of the Shymkent Oil Refinery, operated by PetroKazakhstan Oil Products, which aims to increase oil refining capacity by 6 million tons.

Two additional major KMG projects are related to the second phase of the integrated gas chemical complex and constructing a polyethylene terephthalate production plant in Atyrau, with a combined estimated cost of $7.7 billion. KMG’s partners on these projects are Russia’s Sibur and China’s Sinopec.

The Top 17 projects also likely include the construction of a potassium enrichment and production plant at the Satimola deposit in the West Kazakhstan region. This three-stage investment project, valued at $2.4 billion, is planned through 2035, with beneficiaries including Nurlan Artykbayev and the Singapore-based Qazaq Potassium Pte. Ltd.

Another project, valued at $2.2 billion, led by Andrey Lavrentiev’s Qarmet, aims to increase steel production to 5 million tons by 2028 in Temirtau. Lavrentiev is also involved in constructing a Kia car plant in Kostanay, with a production capacity of 70,000 vehicles per year. In addition to Lavrentiev’s entity, Kia Russia & CIS LLC and Tobol Social Entrepreneurship Corporation (SEC) are co-owners. One other likely project in the Top 17 is Nurlan Smagulov’s multi-brand automobile plant in Almaty, with both automobile projects expected to be completed by the end of 2025.

Another project likely to be on the list is a $1 billion ammonia and urea plant led by Bakharidin Ablazimov’s KazAzot Prime. Production, scheduled to begin by 2026, is expected to expand the export potential of KazAzot, the fertilizer producer operating in Mangystau.

A major metallurgical project, previously mentioned by the Minister of Industry Kanat Sharlapaev as a priority, is a plant for smelting low-alloy special-purpose steels. This plant, estimated at $454 million, is being developed in Karaganda’s special economic zone, with Sergey Pavlinger as the beneficiary. The DBK is currently reviewing the project.

The Top 17 list also includes projects in tourism. Although MNE did not specify details, Kazakhstan’s 2023–2029 tourism development concept highlights three major investment projects. These include the construction of a hotel complex and related facilities in the tourist district of Astana, previously estimated at $2 billion, to be implemented by Ellington Group KAZ Ltd., with ultimate beneficiaries being the government of Kazakhstan (represented by the State Property Committee of the Ministry of Finance) and Singapore’s Star of Ellington Projects Pte. Ltd. The list also likely includes the next phase of Fettah Tamince’s hotel and tourism project in Aktau and the Kaskasu tourism cluster in the Turkestan region, managed by Oirat Mamirov and SEC Turkestan. Both projects are seeking funding from the DBK, with applications currently under review.

If the list identified by Kursiv Research differs from the official one, we encourage the MNE to make the necessary updates.

Champions on the field

This isn’t the first time Kazakhstan’s authorities have pursued priority megaprojects. In November 2007, the government of Kazakhstan launched the «Top 30 Corporate Leaders of Kazakhstan» program, aimed at consolidating the efforts of business and the state to create new industries and upgrade existing ones. The goal was to diversify and enhance the export potential of the country’s non-resource sector. In fact, the program provided political backing for its participants, putting them in priority for financing by national development institutions, primarily by the DBK.

In 2015, another initiative focused on priority projects was introduced under the leadership of Kuandyk Bishimbayev, ex-CEO of Baiterek, a national management holding company. At the time, the holding selected 28 companies to participate in the «national champions» program, with projects worth $765 million intended for financing through development institutions within Baiterek, including the DBK. The effectiveness of this policy came under scrutiny when, following the events of January 2022, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev criticized the DBK, stating that the development institute had become a «personal bank for a select few.»

The creation of the list of 17 megaprojects appears to follow a similar path and is likely to produce similar results. This may explain why officials are hesitant to disclose details of the decision-making process and the list of beneficiaries.

Focusing state policy on «champions» could inevitably lead to accusations that the government favors certain entrepreneurs. An alternative approach would be to consolidate industrial policy measures within a unified program for developing non-resource sectors. In 2009, an attempt was made in this direction with the adoption of the State Program of Industrial and Innovative Development, which replaced the «Top 30 Corporate Leaders» initiative. Although this program allowed for a comprehensive, center-to-regional support system for investments in non-resource sectors, it is unfortunately almost gone. All that is left from that state program is the industrialization map.