What’s behind Kazakhstan’s budget shortfalls?

This year, fiscal reform should be a top priority for Kazakhstan’s government. The cabinet has proposed raising certain tax rates to boost budget revenues and reduce reliance on transfers from the National Fund. These challenging reforms are necessary because Kazakhstan has long pursued a procyclical fiscal policy, increasing government spending even during periods of high oil prices and strong economic growth. Over time, this approach has led to imbalances in public finances. Kursiv Research has analyzed how Kazakhstan established and then circumvented its budget rules, explaining why the current reforms are unlikely to fully resolve these issues.

Why exporting countries must follow a countercyclical policy

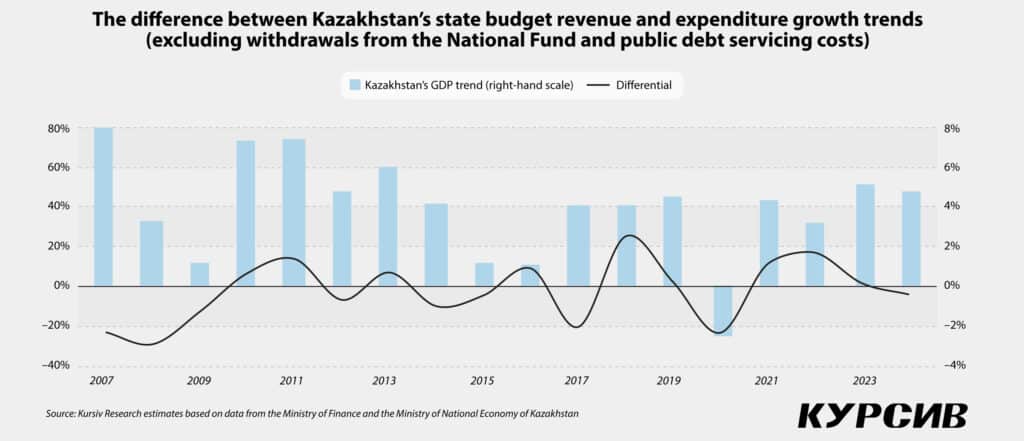

For oil-exporting countries, a procyclical fiscal policy means increasing government spending when commodity prices are high. However, excessive spending can overheat the economy, driving inflation. Another major issue arises when oil prices fall — government revenues decline, forcing spending cuts. This, in turn, reduces aggregate demand and leads to economic stagnation.

Some resource-rich nations adopt a countercyclical fiscal policy to mitigate the negative effects of commodity price cycles and enhance macroeconomic stability. This approach involves accumulating financial reserves during periods of high revenue to support the economy during downturns. To enforce such a strategy, governments establish countercyclical budget rules.

Kazakhstan made its first attempt to manage commodity cycles in 2001 by creating the National Fund, designed to redirect oil sector taxes and other mandatory payments away from the state budget. However, fiscal policy remained largely discretionary, without formal budget rules. Budget rules, first introduced in 2010 and expanded in late 2016, failed to create a countercyclical framework.

In late 2019, Kazakhstan began implementing a countercyclical budget policy, starting with amendments to the National Fund’s operating concept. These modifications introduced an oil cut-off price mechanism to limit guaranteed transfers and prevent excessive withdrawals from the fund. The mechanism relied on conservative oil price forecasts.

However, in response to the economic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the implementation of this policy was postponed until 2023. By then, the original concept had been replaced by the public finance management concept through 2030, approved in September 2022. This new framework conditionally divides fiscal rules into two categories: primary and subsidiary. The previously introduced (but delayed) guaranteed transfer rule and a new national budget expenditure rule were designated as the primary fiscal rules. Together, these regulations, along with additional budgetary guidelines, were designed to promote a countercyclical fiscal policy.

The new fiscal rules were formally integrated into the Budget Code, making them legally binding. These rules have been in effect since 2023. The new concept outlined clear criteria for a countercyclical budget and tax policy, stating that it «not only mitigates the impact of external macroeconomic shocks but also creates additional budget reserves during economic upswings.»

This practice is consistent with the generally accepted strategy for resource-dependent economies: saving during boom times to cushion the economy during downturns. However, in countries that do not rely on natural resource exports, the countercyclical policy serves a different purpose — primarily to prevent economic overheating.

Kazakhstan’s budget policy before the introduction of countercyclical rules

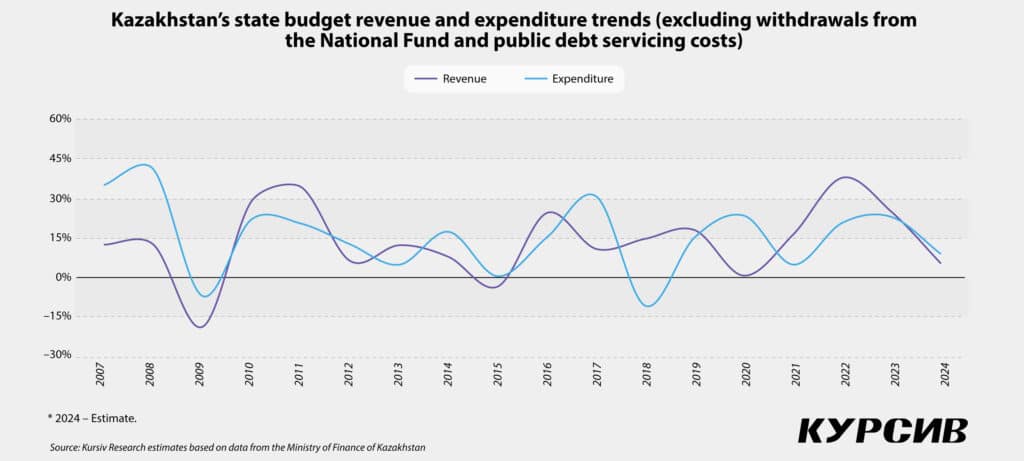

Before the introduction of countercyclical fiscal rules, Kazakhstan’s budget policy was largely procyclical. This pattern persisted both during the period of discretionary policy (before 2011) and under the subsequent fiscal rules (effectively until 2023), which were not designed to be countercyclical.

A key reason for this trend is that resource-rich nations like Kazakhstan often increase public spending based on the relatively stable revenue generated by commodity exports. This can create a boom-and-bust cycle: government expenditures rise during periods of economic growth but must be drastically cut when revenues decline, thus worsening economic volatility.

Research confirms that Kazakhstan’s fiscal policy was procyclical prior to the 2023 reforms. Zhandos Ybrayev, a research fellow at the Economic Modeling Development Center, notes that while the pre-2020 fiscal rules promoted accountability, they did not effectively support long-term economic growth or structural transformation.

A study by the National Bank of Kazakhstan analyzing fiscal policy from 2010 to 2022 further highlights this pattern. The study examined Kazakhstan’s output gap in relation to various fiscal balances (cyclically adjusted, non-oil cyclically adjusted and structural), as well as fiscal impulses. The findings revealed numerous instances of procyclical, rather than countercyclical, fiscal policy during this period. However, the authors noted some countercyclical measures, particularly when the government increased transfers from the National Fund to stimulate economic recovery during recessions.

Notably, these econometric analyses were based on data up to 2022, meaning they do not yet reflect the effects of the countercyclical policy framework.

Did the introduction of countercyclical rules change Kazakhstan’s budget policy?

After adopting countercyclical budget rules in 2023, has Kazakhstan’s fiscal policy actually changed? Experts from Kazakhstan’s Supreme Audit Chamber (SAC) suggest that it has not.

Upon analyzing the government’s 2023 budget implementation report, the SAC concluded that «the cabinet is not adhering to the countercyclical budget policy rule as stipulated in the Budget Code.»

The primary concern revolves around the guaranteed transfer rule from the National Fund, which is determined by the oil price cut-off mechanism.

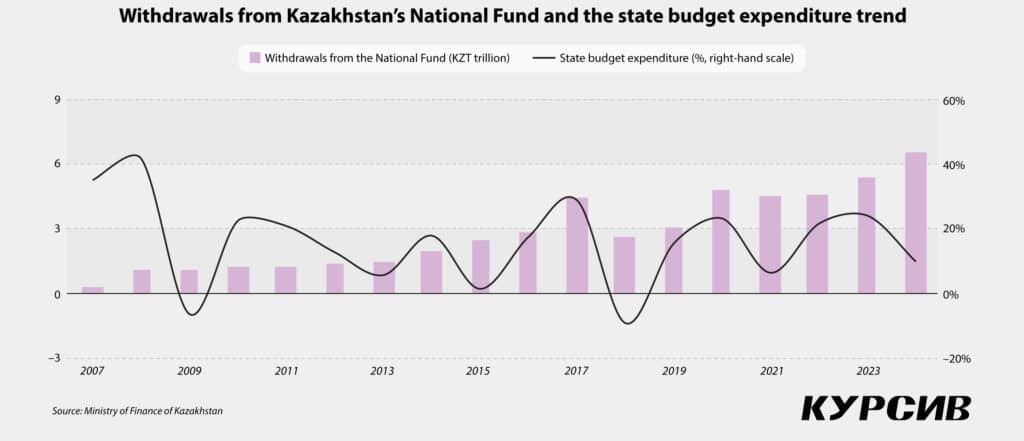

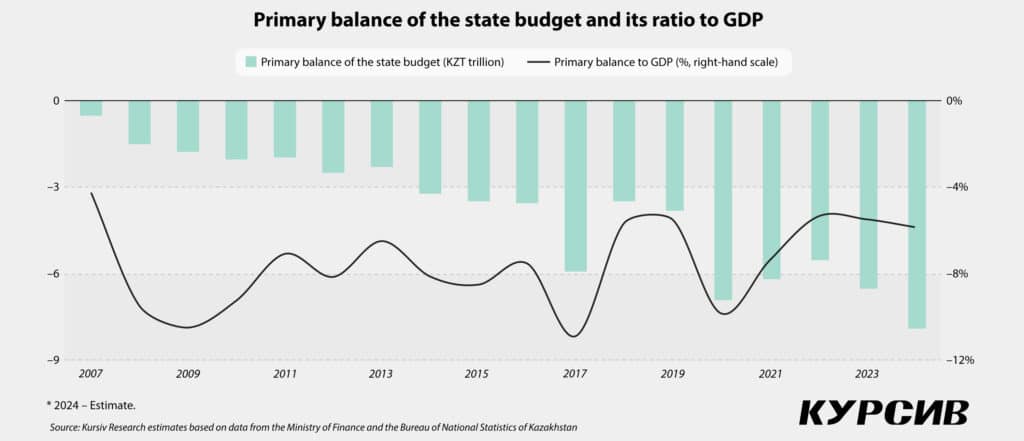

«Despite rising oil prices (from $42.30 per barrel in 2020 to $99.80 per barrel in 2022) and moderate economic growth (4.6% in 2023), transfers from the National Fund remained at critical pandemic-era levels. Government spending continued to rise, contributing to a widening budget deficit of 3.1 trillion tenge (approximately $6.8 billion) in 2023,» the SAC noted.

In 2020, the government received nearly 4.8 trillion tenge from the National Fund as a guaranteed transfer. By the end of 2023, this amount had increased to just over 5.3 trillion tenge (approximately $11.6 billion). This consisted of 2.2 trillion tenge in guaranteed transfers, 1.8 trillion tenge in targeted transfers and 1.3 trillion tenge in dividends from KazMunayGas shares. However, the targeted transfers and dividends were not subject to budget rules, effectively making their withdrawal unregulated.

State auditors warn that the absence of limits on targeted transfers threatens the National Fund’s long-term savings function. This loophole has allowed targeted transfers to rise significantly:

- Approximately $1.2 billion in 2022, before the introduction of countercyclical rules.

- Nearly $4 billion by the end of 2023, despite the guaranteed transfer rule being in effect.

- Over $7 billion in 2024.

Beyond these transfers, in 2024, the state budget also received an additional $2.5 billion in dividends, some of which came from a stake in Kazatomprom, acquired using National Fund money. According to estimates by Kursiv Research, by the end of 2024, Kazakhstan’s government could receive up to $13 billion from the National Fund, the highest amount in absolute terms since the fund’s inception.

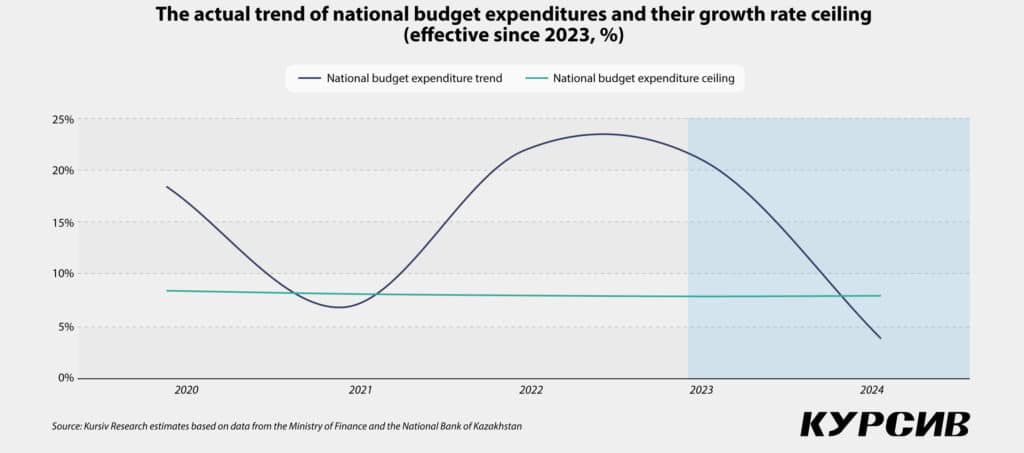

Auditors from the SAC argue that the second primary fiscal rule, which limits national budget expenditure growth, does not effectively ensure countercyclicality. The issue stems from the methodology outlined in the current Budget Code, where the growth rate of national budget expenditures for the planning period is linked to long-term economic growth, adjusted for the inflation target.

During periods of strong economic performance, expenditure limits are high, allowing for increased spending. During economic downturns, expenditure limits are low, restricting government spending when stimulus might be needed most. State auditors highlight that this structure encourages procyclical spending patterns: expanding expenditures in good times but failing to restrain them adequately.

What measures are needed to achieve countercyclicality?

While SAC auditors criticize the current system, they also offer broad recommendations to enhance budget sustainability and balance, though without providing specific details. Their 2023 report suggests:

- Introducing covenants to limit targeted transfers from the National Fund.

- Establishing a fixed share of expenditures that must be directed toward development and investment projects.

The issue of excessive withdrawals from the National Fund through targeted transfers is on the cabinet’s agenda.

«As part of coordinating fiscal and monetary policies, we have been in discussions with colleagues from the ministries of finance and national economy about extending the budget rule to all types of withdrawals from the National Fund. Currently, only guaranteed transfers are covered, while targeted transfers remain exempt. We have reached a fundamental agreement that the budget rule will apply to all withdrawals — including guaranteed, targeted and others— capping them at a specific percentage. Consultations are still ongoing,» said Timur Suleimenov, the head of the National Bank, at a briefing held on Jan. 17, 2025.

He did not list specific parameters, the percentage cap or its calculation since consultations with the cabinet are still in progress.

Research suggests that the effectiveness of countercyclical budget policies depends on two key factors: the strictness of the rules and the quality of public administration. Moreover, to achieve countercyclicality, both factors must function simultaneously. High-quality public administration with soft rules does not produce results, while strict rules will not be implemented effectively with weak management.

In this context, the government should avoid using «escape clauses,» which are conditions built into fiscal rules that allow for adjustments or suspension. Following a mission in the fall of 2024, International Monetary Fund experts recommended eliminating escape clauses and establishing an independent fiscal council while also implementing stricter provisions to prevent the suspension of budget rules.

For example, the Ministry of National Economy’s current forecast for Kazakhstan’s socio-economic development for 2024-2028 explicitly states that the 2023 national budget expenditures were projected without applying the budget rule to limit expenditure growth. These temporary exemptions are linked to the adoption of additional obligations for implementing regulations related to public administration system changes expected in the first half of 2025.

In addition to eliminating escape clauses, it is crucial to revise the design of the budget rule on expenditures to better align with the needs of the domestic economy. Rather than tying the growth rate to the previous decade’s economic growth, it should be limited based on factors such as budget revenues (either total or non-resource revenues) or past expenditures. Global best practices offer different configurations of this rule. In some models, only the growth of specific expenditure types is restricted — current expenditures are strictly controlled, while investment expenditures may have more flexible limits.

How will the tax and budget reform affect the situation?

Soft budget constraints inevitably create problems in public finances, forcing the government to adjust its tax and budget policies. In January 2025, Serik Zhumangarin, minister of national economy and deputy prime minister, proposed several key tax changes:

- Increasing the value-added tax (VAT) rate from 12% to an estimated 16% to 20% (final rate yet to be determined).

- Lowering the VAT registration threshold from approximately 79 million tenge to 15 million tenge ($30,000) per year.

- Reducing the number of special tax regimes currently available to many small and medium-sized enterprises.

The cabinet projects that these measures will generate an additional 5 to 7 trillion tenge (approximately $13 billion) in budget revenue. At an extended government meeting on Jan. 28, 2025, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev endorsed the reform.

«I agree that reform is necessary. However, we now face the challenge of reducing transfers from the National Fund and strengthening its savings function. The accumulated funds should be used to finance large infrastructure projects,» Tokayev said.

The president and the cabinet expect these additional revenues to reduce withdrawals from the National Fund and decrease the budget deficit. However, without well-designed budget rules and strict adherence to them, a significant increase in treasury revenues could lead to an equally high, or even higher, expenditure growth rate. If that happens, Kazakhstan could find itself back where it started, with an unsustainable budget imbalance forcing the government to implement another round of radical tax increases.