More human than we knew: What Jane Goodall and the chimps taught us about ourselves

On Oct. 1, pioneering primatologist Jane Goodall passed away at the age of 91. Her discoveries forever changed how we understand both chimpanzees and our own place in the natural world.

As literary critic Alexander Gavrilov wrote to Novaya Gazeta, Goodall broke down barriers — between species, between humans and chimpanzees, and between the observer and the observed.

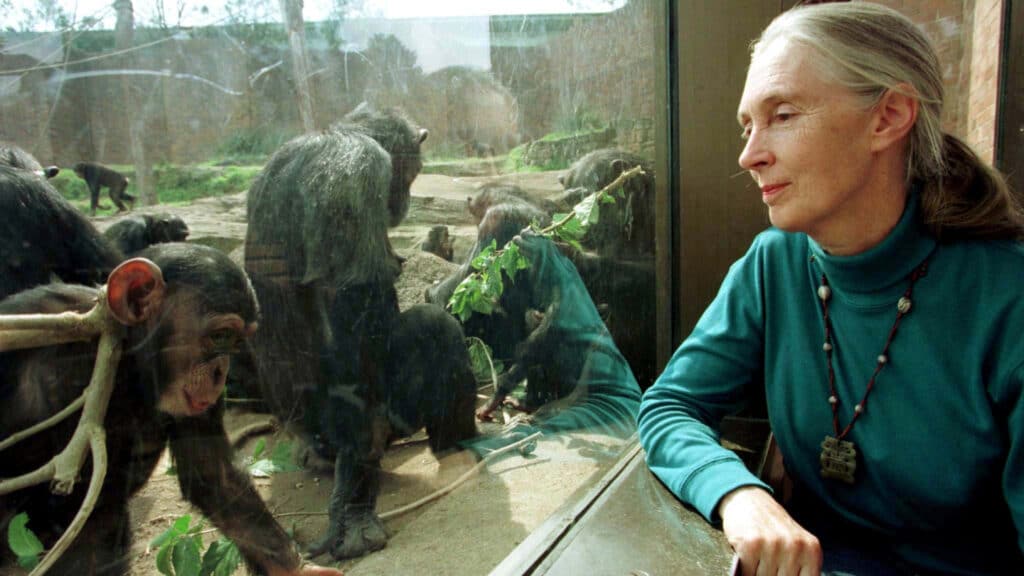

Before Goodall, most scientists studied animals from a distance — often in zoos, removed from their natural habitats. Goodall did the opposite: she went into the forests of Tanzania to live among the chimpanzees themselves.

Breaking the human–animal divide

At the time, scientists believed that nonhuman primates were incapable of emotions, forming long-term relationships or using tools. Goodall’s meticulous fieldwork proved otherwise.

She was the first person to observe chimpanzees using tools — sliding sticks into termite mounds, waiting for insects to crawl on, then licking them clean.

That simple act upended centuries of assumptions about what separates humans from other species.

Goodall also revealed darker truths. She documented how chimpanzees wage war, display cruelty, and even kill members of their own groups — not for food or survival, but seemingly out of aggression or dominance.

Her findings shattered the comforting idea that only humans were capable of such behavior.

We like to think of ourselves as unique — the only creatures capable of love or hate, nobility or treachery. But Goodall showed that apes share our capacity for both kindness and cruelty.

The dismantling of human exceptionalism that Charles Darwin began could not have been completed without her work, Gavrilov observed.

Science as activism

Goodall’s scientific contributions naturally evolved into activism.

If chimpanzees can think, feel, and form complex societies, she asked, what gives humans the right to destroy their habitats?

Her research became a moral call — one that linked science directly to environmentalism:

«This planet has many masters and inhabitants. Humans are only one of them — and not necessarily the most important.»

For Britain, Goodall’s life also carried a feminist message.

Goodall proved that a woman could be both a scientist and explorer, forging her own path far from convention. She married twice: she divorced in 1974 and lost her second husband to cancer in 1980. She had one son.

A legacy of peace with nature

Notably, even her name, «Goodall,» seems fitting. It evokes something ancient — goodness itself, like the «good book.»

In that sense, she stood among those rare souls who have tried to reconcile humanity with the living world: like St. Francis of Assisi, who preached to the birds, or St. Anthony of Padua, who preached to the fish.

Jane Goodall went further. She didn’t preach to the apes — she preached peace with them to us.