Kazakhstan is keeping pace with international film festival trends. Recently, the country launched a festival featuring the latest works by women directors. The organizers even managed to showcase Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine as Light, an Indian tale of love and sisterhood that won this year’s Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival, as well as Molly Manning Walker’s How to Have Sex, a winner of the Cannes’ «Un Certain Regard» competition.

However, the most well-attended screenings were for films by local directors, highlighting Kazakhstan’s growing pool of talented filmmakers. Among these are Tul by Sharipa Urazbayeva, Madina by Aizhan Kassymbek (which was showcased at the Tokyo Film Festival and earned its director of photography, Aigul Nurbulatova, the national «Critics’ Choice» award), Malika Mukhamedzhan’s debut film The Swallow (featured at the Shanghai Film Festival) and finally, Assel Aushakimova’s satirical piece Bikechess, which won the International Narrative Competition at the Tribeca Festival in New York. This last film merits additional consideration.

Queer and fem films recognized in America

Winning at the Tribeca Film Festival, an event organized by Robert De Niro himself, is a significant honor—particularly in the prestigious International Narrative Competition. For Assel Aushakimova, a former bank clerk who transitioned into filmmaking to tell stories that resonate with her, this achievement marks a major milestone. Bikechess is her second feature film.

Aushakimova’s first feature, Welcome to the USA, centers on a lesbian who wins a green card and grapples with the decision of whether to leave Kazakhstan or stay. Despite its queer themes, Welcome to the USA managed to secure distribution in Kazakhstan. It was rated 21+ and given a limited release in just a few independent theaters, with screenings scheduled for late-night showings — after 10:00 p.m. The limited release was largely due to a scene featuring a kiss between two girls, which kept the film out of reach of the public at large.

Queer themes are central to Aushakimova’s work and her films now align with the broader context of most contemporary film festivals. Aushakimova is an independent filmmaker, often financing her projects herself or through grants from international foundations. Before securing funding for her latest project, she participated in four international film markets, including the «Work in Progress» section at the Karlovy Vary Film Festival, where she presented a rough cut of her unfinished film. Eventually, her second film was produced with support from Norwegian and French foundations. The only producer from Kazakhstan involved was Almagul Tleukhanova, best known for Abdel Fiftibayev’s melodrama Boyzhetken. Vsyo iz-za neyo.

‘Bikechess’ is about…

It’s hard to ignore that Bikechess serves as a fictional monument to the absurdity of Kazakhstani reality, depicting blatant corruption — a topic Assel Aushakimova often addresses on her social media — alongside contrived government programs and their surreal portrayal in Kazakhstani media, creating the impression they originate from a parallel universe. Yet, in these «critical» pieces set in this Wonderland, the central issue isn’t the abuse of power by authorities or large-scale embezzlement, but rather the «dangerous» feminists and LGBT activists who hold rallies to assert their rights to their bodies.

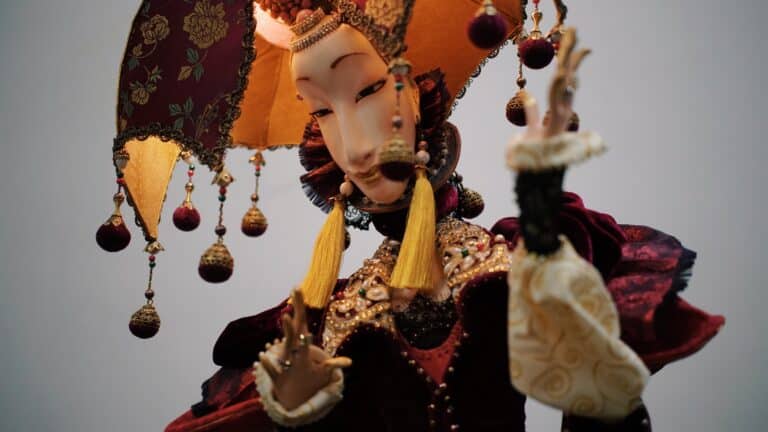

The film, shot by renowned cinematographer Aidar Ospanov, centers on Dina (Saltanat Nauruz), a female journalist from a Kazakh state TV channel with the «Nur» prefix in her name. Her reports are detached from everyday reality. In the opening scene, Dina covers the invention of a bizarre new sport called «bikechess,» which combines intellectual and physical challenges by having a player make a move on a chessboard and then pedal. In an interview with Vlast.kz, Aushakimova revealed that she came across a news article about bikechess and found the concept so absurd that she decided to base her comedy-drama on it. Fortunately, there was no shortage of similar stories and Aushakimova was able to gather a dozen of them to build the film. For instance, Aushakimova replicates a news segment about a state program for the «modernization of national consciousness» that aired on a Kazakhstani TV channel.

Throughout Bikechess, Dina reports on imaginary problems rather than real ones — such as public receptions featuring a bored policeman sitting at a table in an empty parking lot to demonstrate government «helpfulness» or a local scholar claiming that all life on Earth originated in Kazakhstan. The film depicts surrogate science, imitations of aid to citizens and confrontations with activists — even those protesting with a blank poster. These everyday absurdities are plentiful in Bikechess, presented not with anger or sarcasm but with irony. The final scene, revealing a genuine tragedy, shifts the narrative entirely.

What impressed the Tribeca jury in Bikechess? Perhaps it’s the dark charm of Kazakhstan’s unique brand of absurdity. While it may seem ordinary to those familiar with it, it’s likely something new to outsiders. Interestingly, some Western reviews of Bikechess have pointed out another Kazakhstani absurdist director, Adilkhan Yerzhanov. While Yerzhanov’s darkly humorous social critiques are set in the fictional village of Karatas, Assel Aushakimova focuses on documenting reality, particularly from the perspective of underprivileged citizens. Despite their different artistic approaches and efforts to distinguish themselves, both directors use absurdity as a form of artistic expression.

Bikechess stands out for its fresh perspective: it eschews rural scenes and the hardships of provincial life, focusing instead on city dwellers who participate in rallies, fight against discrimination and advocate for their right to self-identify.

Why the queer theme?

The LGBT theme in Bikechess is central to the storyline of Dina’s younger sister, Zhanna (Assel Abdimavlenova), a lesbian activist who frequently clashes with authorities. Dina fully supports her sister: she accepts Zhanna’s romantic choices, shows genuine interest in her girlfriend and even smiles at the sight of new art objects in her kitchen — hygienic pads smeared with red paint that Zhanna plans to use as visual aids in her rally. Dina also bails her sister out of pre-trial detention, though she avoids covering Zhanna’s activities in her reports due to censorship. The most the activists can hope for is harsh criticism on social media and condemnation from passersby for lacking honor and «uyat» (the Kazakh word for «shame»).

What initially appears to be just another episode of Kazakh life takes a dramatic turn when one of the detained girls dies. Yet, Dina remains oblivious, continuing her series of absurd reports, which highlights the disconnect between her world and the harsh realities faced by her sister and the activist community.

As Assel Aushakimova explained to Vlast.kz, making queer-themed films in Kazakhstan is incredibly challenging, despite her advocacy for better representation and normalization. It required substantial effort to find actresses willing to take on even relatively benign roles. One popular young actress initially agreed to participate but withdrew when faced with a scene involving a kiss between two women, citing discomfort with the content.

Will Bikechess be released in Kazakhstan?

The screening of Bikechess on Qyzqaras is more of an exception than the norm, offering a rare opportunity to see the film on the big screen. While a local private network might eventually pick it up, this would be an exception rather than the rule. Directors like Assel Aushakimova are unlikely to achieve widespread popularity or substantial state support in Kazakhstan, especially given her outspoken, often radical critiques of everyone from officials to fellow filmmakers. However, Aushakimova’s prospects might not depend on domestic support for long. With international recognition, including her significant win at Tribeca, she is well-positioned to break into larger cinema circles. This acclaim could open doors to more opportunities on the global stage.