Over two days — Nov. 27 to Nov. 28 — the exchange rate of the tenge fell by 4%. On Wednesday, it dropped to 500 against the dollar and nearly reached 520 on Thursday. Moreover, all of this occurred amidst high trade volumes — about $1 billion over two days.

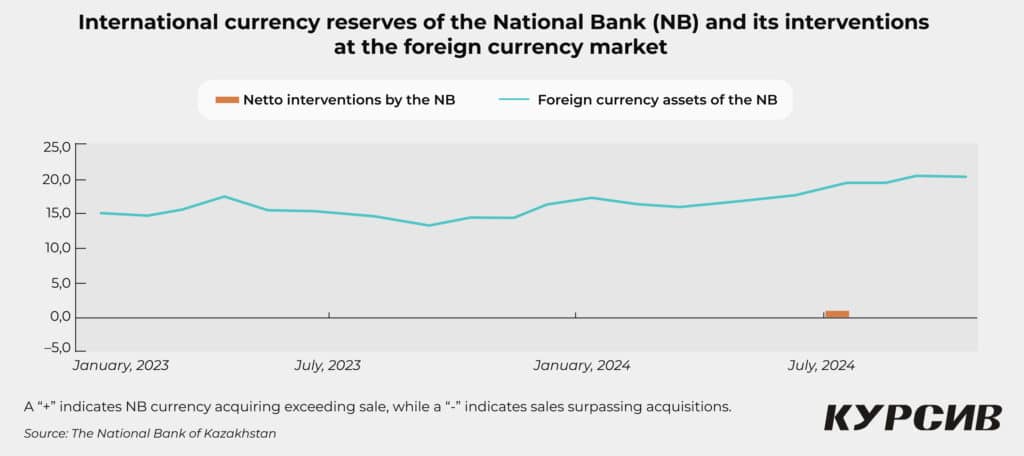

In this situation, the regulator must make tough decisions that will shape Kazakhstan’s economy in the coming days and in the medium-term spanning from several months to a few years. First of all, this involves a decision about interventions in the foreign currency market. Secondly, on Nov. 29, the National Bank of Kazakhstan was expected to announce a new base rate that will mark the beginning of the new 2025 year.

This is not going to be an easy decision, as the political leadership, businesses and the population expect the monetary regulator to deliver effective and balanced solutions. Even though this equation is complex, it is realistic to find a viable path forward.

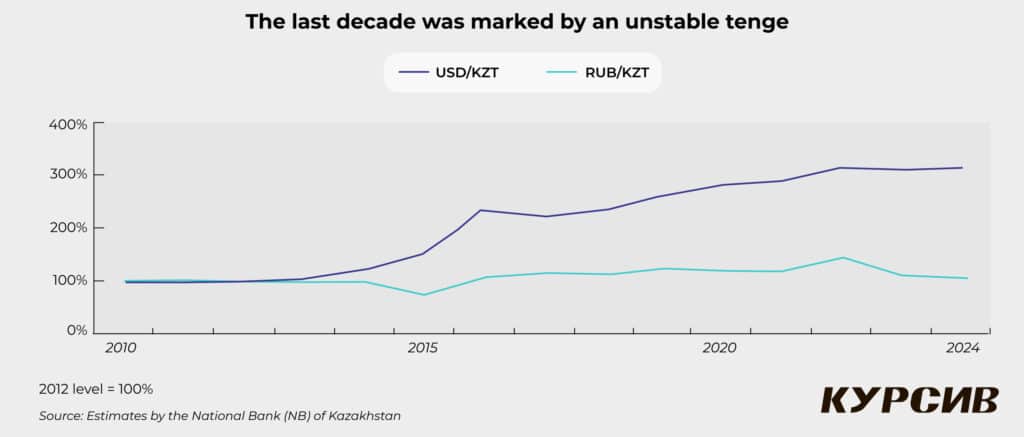

Firstly, we need to turn back and critically assess the monetary policy and exchange rate approach we have implemented over the past nine years. We must ask ourselves: does a fully flexible exchange rate bring the desired benefits? Has inflation decreased since the transition to inflation targeting? The answer is no. Have we prevented the depreciation of our national currency? No again. Instead, over the past eight years, we have seen more expensive loans and a higher tempo of currency weakening, even though inflation has remained almost the same and has never reached its target.

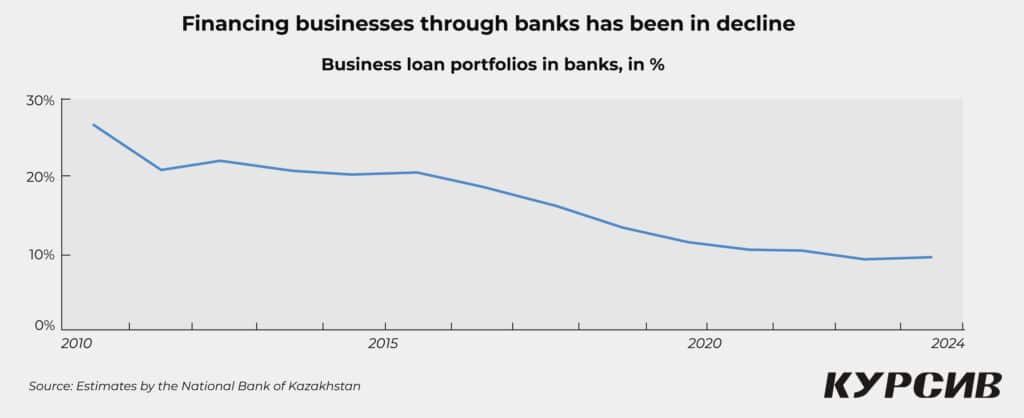

Corporate lending has declined to an inadequate 11% of GDP, compared to 55% in Russia, 50% in Brazil and 166% in China. As a result, businesses have grown more dependent on public subsidies, the budget deficit has soared sharply and the banking system has reported temporary, risk-free profitability.

Harsh fluctuations in the USD/KZT and RUB/KZT exchange rates invariably create a series of shocks for economic actors. This uncertainty has caused many local companies to delay their investment plans, while the quasi-public sector and exporters have been incentivized to speculate in the foreign currency market. Meanwhile, the population has sought to keep their savings in «hard money.» Furthermore, sharp devaluation of the tenge has accelerated inflation, as market participants raise prices during periods of devaluation and never lower them when the tenge strengthens.

The free float of the tenge has only been advantageous when the currency’s exchange rate was stable due to various factors. Significant dedollarization in recent years has occurred because of two key factors: the state-controlled exchange rate of the dollar and the high base rate. It is essential to preserve these results, particularly as the National Bank’s reserves remain at an adequate level — approximately $20 billion as of October, which is a 22% increase since the beginning of the year. This is the highest level since the summer of 2017. Combined, the National Bank, the National Fund and the Unified Accumulative Pension Fund (UAPF) possess over $117.9 billion in reserves ($40.5 billion + $62.6 billion + $14.8 billion). However, the UAPF, which buys foreign currency on the open market, creates a significant imbalance in the market, facilitating the rapid depreciation of the tenge.

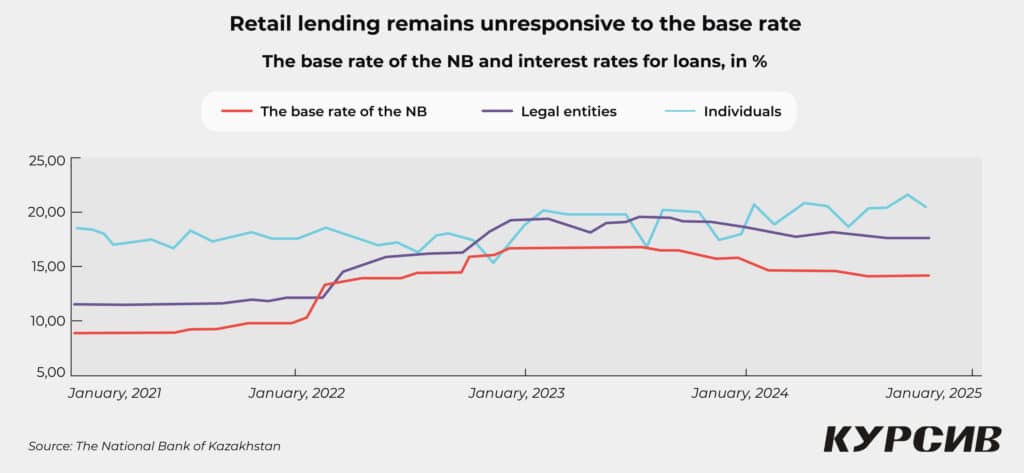

This is the right time for countercyclical fiscal policy: by accumulating resources during good times and refraining from spending them during crises, we strengthen economic potential. Unfortunately, we see that the interest rate channel is ineffective as nearly no one reacts to it. Large businesses avoid taking loans at current rates, small and medium-sized enterprises rely on subsidies, the unsubsidized mortgage market has almost disappeared and consumer loans are issued at interest rates far above the National Bank’s base rate. We face similar problems with the savings channel.

The majority of deposits belong to the quasi-state sector and the wealthiest 1%, while 90% of the population don’t care about deposit rates and have no savings. Even wealthy individuals are more concerned about the volatility of the exchange rate and show weak interest in deposit rates. Do we realistically expect people and companies, who rushed to buy dollars last week, to stop doing this because deposit rates rose from 14% to 16%? For example, the demand for investment assets rarely declines even if their prices rise. Foreign currencies and stocks become even more attractive when their value grows. There are good studies supporting this observation.

Once again in modern Kazakhstani history, we are at a crossroads. If the National Bank decides to stick to its current template, the economic situation may worsen even more.

We can avoid a Catch-22 by injecting public money into the economy with one hand while devaluing it with the other. In such a situation, the percentage revenue on tenge-denominated deposits merely converts into greater demand for foreign currency. Naturally, this does nothing to slow inflation. Moreover, people’s lack of confidence in the tenge cannot be bolstered with ultralow interest rates on foreign currency deposits and high rates on tenge deposits.

For some, a weak tenge that easily slips into free fall whenever negative externalities occur may seem like an effective solution benefiting exporters and domestic manufacturers. This, however, is not true. In reality, it is a mechanism designed to reduce social obligations, with the price being skyrocketing costs for investment projects. Affordable credit facilities would provide far better support for manufacturers.

It would not be wise to replicate the Bank of Russia’s approach. Russia cannot conduct active interventions because it cannot use its gold and currency reserves. Its economy is large and closed, and its labor market is overheated due to rapid growth in nominal incomes. Not all mechanisms that work well for large economies are suitable for smaller economies. For instance, inflation targeting works effectively in the U.S. but is far less effective in Kazakhstan.

The government and the National Bank should stop avoiding responsibility and finger-pointing. They must act together, seeking compromises. Cutting public spending without addressing fundamental problems will not double GDP but will shrink it in real terms as the currency weakens. This will jeopardize President Tokayev’s goal of ensuring exponential economic growth.

Is our market capable of reflecting macroeconomic changes by adjusting supply and demand? What role do speculative factors play in shaping the foreign currency rate and inflation in our country? It seems that the activities of the UAPF in acquiring foreign currency or the National Fund selling foreign currency have a greater impact on the market than changes in the trade balance. This also prevents the exchange rate from reaching a well-balanced ratio.

Meanwhile, speculation by large economic agents and quasi-state companies continues to add uncertainty to the foreign currency market. We cannot «protect» our manufacturers by devaluing the labor of our citizens, yet this is precisely what happens during periods of tenge weakening.

This might be the right time to consider alternative options for managing foreign currency and financial markets. Some methods that have helped countries like Azerbaijan, Vietnam and Armenia reduce inflation and achieve stable economic growth may also work for Kazakhstan. Large economies like China and the UAE, which have controllable free float or near-fixed exchange rates with active regulatory intervention, could serve as examples. Perhaps it is time to move away from the free float policy and allow the regulator to make exchange rate fluctuations more controllable. Narrowing the gap with U.S. Federal Reserve rates from 7-8% to 2-3%, as Azerbaijan has done, could also help. If such changes are made, Kazakhstan’s market could thrive by attracting funds not only from trade or government sources but also from broader economic activity. Otherwise, we will remain dependent on the policies of our neighbors, importing their inflation.

We must also recognize that we can protect our national economy through non-tariff methods. However, we will not master these strategies until there is an urgent need for them.