A shadow over education and healthcare: Kazakhstan’s hidden economy

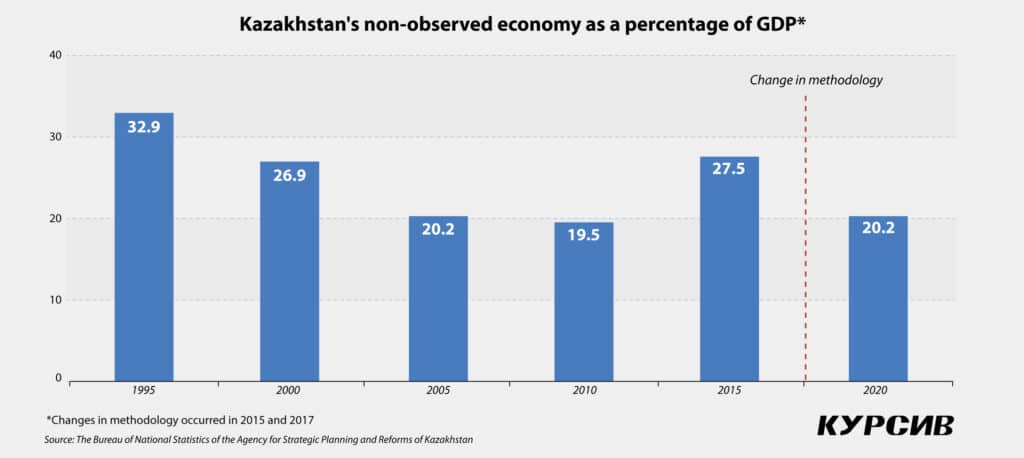

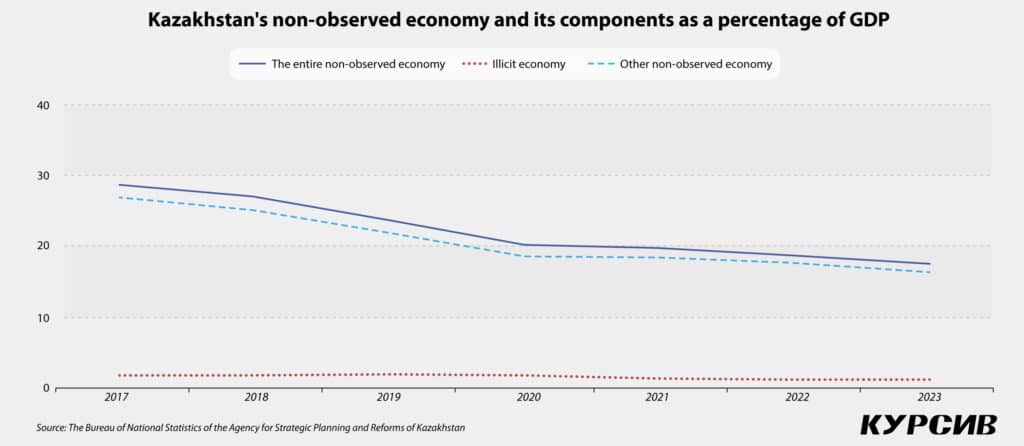

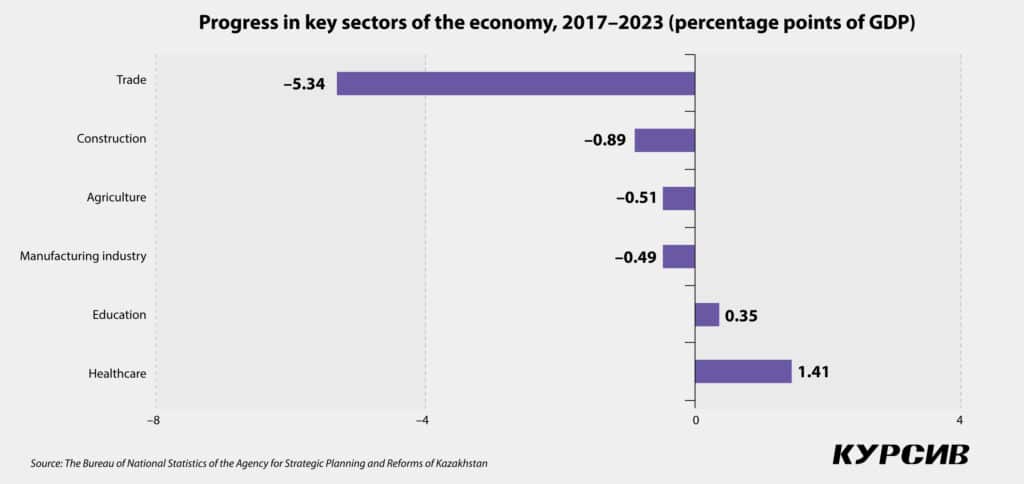

According to official statistics, the share of the shadow economy in Kazakhstan has continued to decline for seven consecutive years. By the end of 2023, the Bureau of National Statistics (BNS) recorded a decrease of 1.26 percentage points (p.p.), bringing it to 17.52% of GDP. However, the shrinking of the shadow economy is a non-linear process: while there have been successes in the trade sector, where the non-observed economy shrank by more than 5 p.p., the indicator increased in the education and healthcare sectors.

Shadow economy under scrutiny

Kazakhstan’s authorities have repeatedly emphasized the importance of bringing the economy out of the shadows, particularly during challenging times when the government sought to boost budget revenues through increased tax collection. For the first time, the goal of reducing the shadow economy was officially outlined at the highest level six years ago. In his October 2018 state-of-the-nation address, Nursultan Nazarbayev, Kazakhstan’s first president, set a target to reduce the shadow economy by 40% within three years.

After recovering from the Covid-19 pandemic, Kazakhstan’s cabinet adopted a comprehensive action plan (2021–2023) to combat the shadow economy, aiming to reduce the non-observed sector to 18.2% of GDP. In setting these targets, Kazakhstan looks to developed countries, where the non-observed economy is estimated to range from 10% to 20% of GDP.

The key tools for implementing the plan included enhancements to customs procedures (such as adopting the Astana-1 information system for customs administration), combating fraudulent invoices and introducing labeling and traceability systems.

In July 2023, the cabinet adopted a new plan for 2023-2025, aiming to reduce the share of the informal economy to 15% by 2025. The plan includes target indicators for the most critical sectors of Kazakhstan’s economy from a regulatory standpoint: domestic trade, transportation and warehousing, manufacturing, agriculture and real estate transactions.

The tools for combating illicit trade include developing a labeling and traceability system, introducing digital solutions for VAT administration to prevent fictitious transactions and implementing taxation for online platforms. In the transportation and logistics sector, plans focus on digitizing transportation documents and rolling out electronic ticketing systems. In the manufacturing industry, major refineries will install electronic scales with online data transmission to the State Revenue Committee regarding oil product shipments.

The crackdown on shady businesses is especially crucial for the government today, as Kazakhstan faces a budget crisis for the second year in a row. With revenues falling short, the government needs to identify new sources of tax income.

In July, a government meeting chaired by Prime Minister Olzhas Bektenov focused on combating the shadow economy. The meeting was attended by heads of respective ministries, representatives from national companies and the National Chamber of Entrepreneurs «Atameken.»

President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev is closely overseeing the reduction of the non-observed economy. The fight against the shadow economy was highlighted in a report following a meeting between the president and Zhanat Elimanov, chairman of the Financial Monitoring Agency, last September.

Calculation, adjustment and recalculation

In statistics, the non-observed economy refers to economic activities that are not captured when collecting data from the primary sources used to compile national accounts. This includes deliberately unregistered producers (type N1), illegal producers (N2), producers not required to register (N3), unsurveyed firms (N4 and N5), producers who deliberately misreport (N6) and «other statistical deficiencies» (N7a and N7b).

The share of the non-observed economy is a metric calculated by official statisticians after analyzing various sets of statistical and fiscal data.

Сurrent BNS methodology specifies that «data from the Bureau, the Ministry of Finance of Kazakhstan and administrative sources are used to directly or indirectly estimate the non-observed economy, providing a foundation for reliable calculations.»

While examining the orderly rows of official statistics might suggest that the shadow economy in Kazakhstan is steadily shrinking, a closer look reveals a more complex picture. According to the BNS, the shadow economy accounted for 17.52% of GDP in 2023, down from 18.78% in 2022 and 28.75% in 2017. However, a less optimistic view emerges when considering earlier official estimates. For example, in 2013, the bureau estimated the shadow economy at 28.3% of GDP. It is worth noting that the methods and sources used by statisticians have expanded since then. Therefore, the 2017 assessment was 2.91 p.p. higher than in 2016, although, admittedly, there were few changes in Kazakhstan’s economic daily life.

The shadow economy also includes the illegal or criminal economy. According to the BNS’s latest estimates, its share in Kazakhstan by the end of 2023 was 1.12% of GDP, down from 1.15% in the previous year.

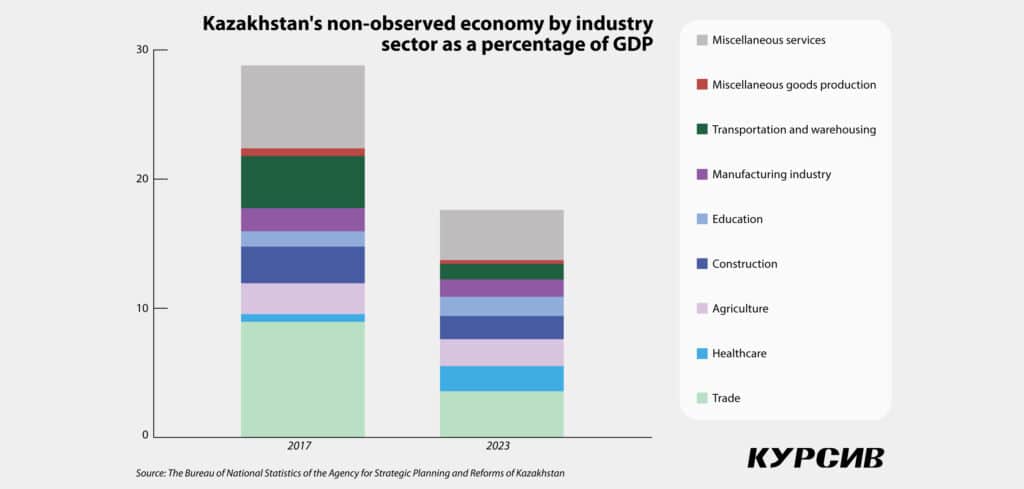

The largest illicit turnover is observed in trade. By the end of 2023, the BNS estimated the shadow economy’s share in trade at 3.53%. Since 2017, the net decrease in this indicator has been 5.34 p.p. This is often attributed to the sale of counterfeit and smuggled goods. According to the Naqty Onim portal, which is linked to the operator of the traceability and labeling system (a division of Kazakhtelecom), the share of the shadow market for tobacco products in 2023 was 10% (or $70 million), for drugs it was 25% ($278 million) and for shoes it was 40% ($168 million).

When we examine the results of the domestic trade sector in light of the goals set in the comprehensive plan to counteract the shadow economy through 2025, trade has already met its target of reducing shadow activities to 5% of GDP.

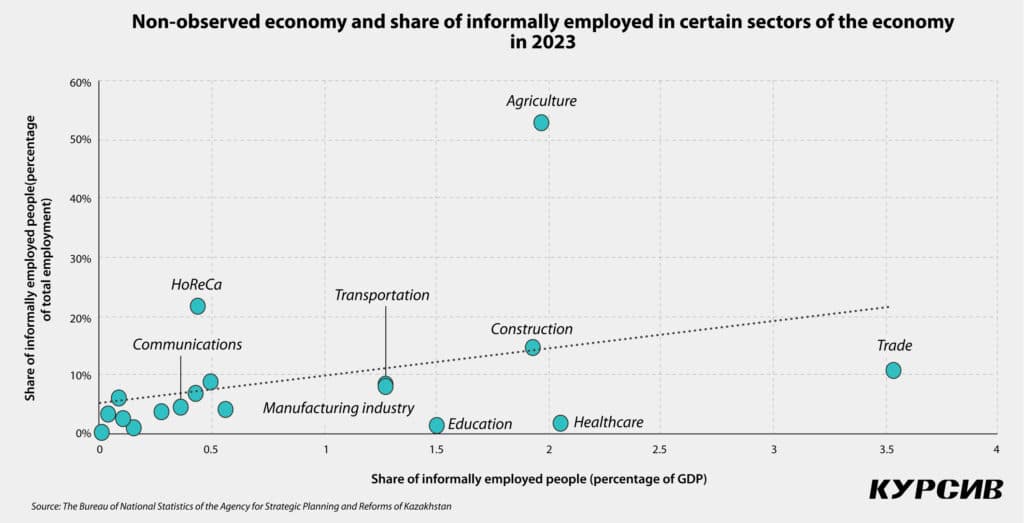

Over the last seven years, the share of non-observed production has decreased in construction (-0.89 p.p. to 1.92% of GDP), agriculture (-0.51 p.p. to 1.96%) and manufacturing (-0.49 p.p. to 1.27%). It appears that the government’s efforts to digitalize regulatory procedures and market mechanisms are slowly but steadily beginning to take effect.

By 2025, the share of shadow activities in transportation should be reduced to 2.4% of GDP (currently 1.27%, which is below the target). In agriculture, the target is 1.4% (though the 2023 figure is already above the target), and in manufacturing, the target is 0.9% (with the current figure above the target).

However, the generally positive picture presented by official statistics is disrupted by two sectors where the state traditionally plays a dominant role: healthcare and education. The share of shadow medical services was estimated at 2.04% of GDP in 2023, an increase of 1.41 p.p. since 2017. Given that healthcare accounts for 2.9% of GDP in gross value added (GVA), illicit turnover now represents just under two-thirds of all medical services provided in the country. A similar situation exists in education: the share of the shadow economy was estimated at 1.49% of GDP in 2023, reflecting a 0.35 p.p. increase since 2017. It is important to note that the share of education in GVA was estimated at 4.7% in 2023.

Informal turnover in both sectors has long been widely known, but the true scale is only now becoming clearer, as a significant portion of peer-to-peer transactions has moved online, enabling tax authorities to track these transfers more effectively.