Have you ever wondered where your hometown or region got its name, and what stories are hidden behind the names of capitals and major cities? A recent project from Kazakhstan highlights how data-driven methods, combined with modern visualization techniques, can shed light on these onomastic mysteries.

Kazakh city names

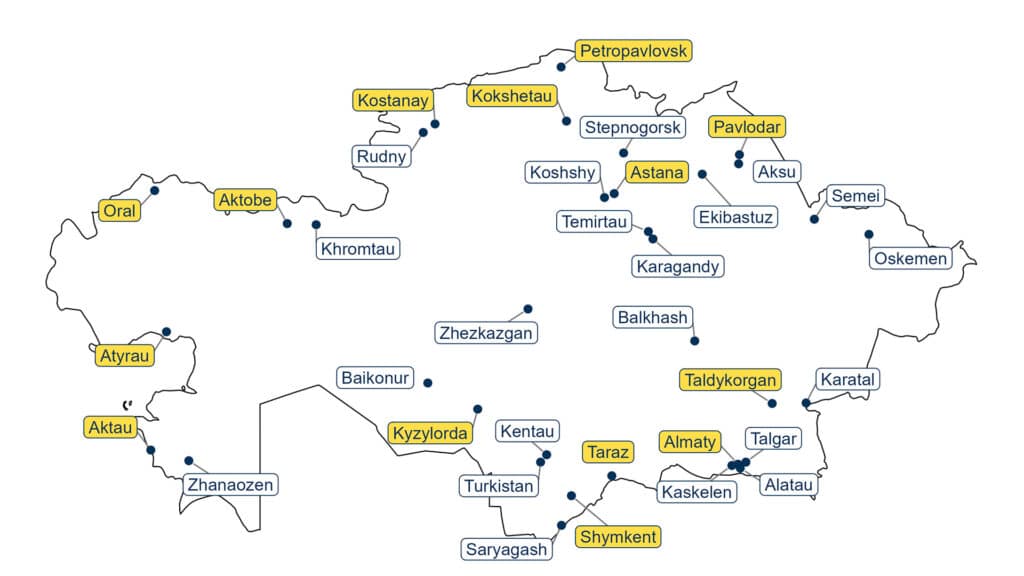

Nurasyl Abdrazakuly, a Kazakh data scientist with a passion for transforming raw data into meaningful insights and compelling visuals, has created a map that translates the literal meanings of city names across Kazakhstan into English.

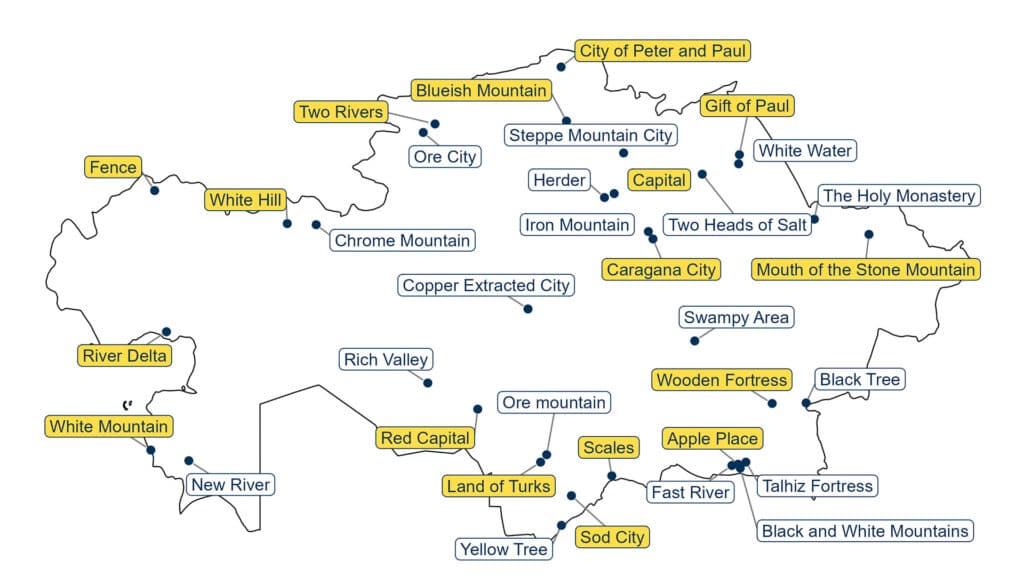

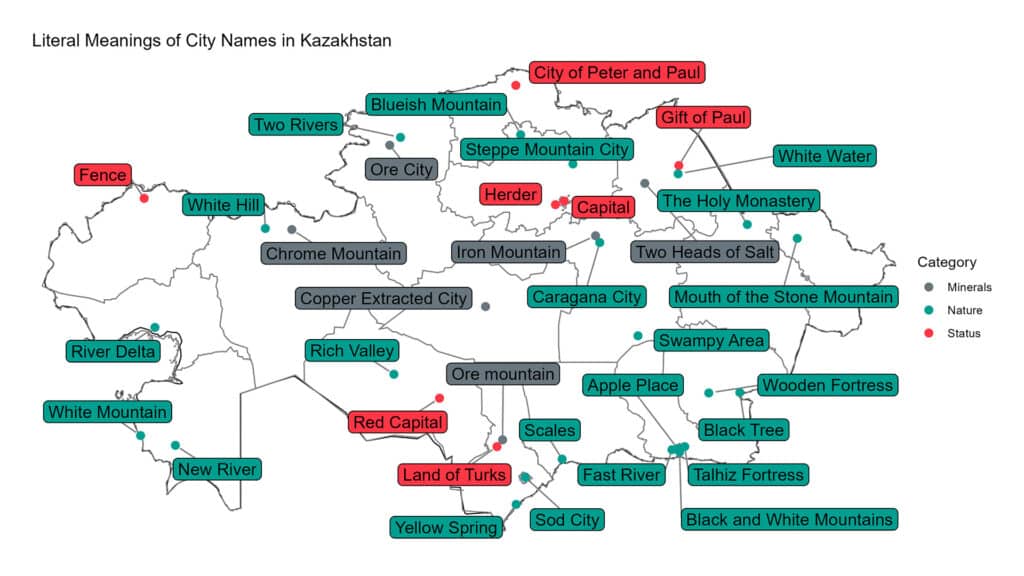

Nurasyl’s visual map reveals that many Kazakh city names are rooted in natural landscapes and poetic imagery, while others reflect the value of local resources or carry political and historical significance.

For instance, Kazakhstan’s largest metropolis, Almaty, literally means «apple place» (from alma, the Kazakh word for «apple»), while the capital, Astana, simply means «capital.»

The central city of Zhezkazgan, a major mining hub, translates to «place where copper was dug» — a fitting name, as the region holds Kazakhstan’s largest copper and manganese deposits.

Some names may come as a surprise. For example, the city of Oral in western Kazakhstan translates as «fence.» The name is derived from the ancient Turkic root or or ural, meaning fence, enclosure or border.

Meanwhile, the miners’ capital of Karaganda (also spelled Karagandy or Qaragandy in Kazakh) is often misunderstood. It doesn’t mean «black blood» (kara meaning «black,» qan meaning «blood») or «while looking,» as mistakenly assumed from a similarly sounding Kazakh word. Instead, the name comes from qaragan (Caragana arborescens or “pea shrub”), a native shrub, and means «place of qaragan bushes.»

Visual mapping trend

The idea for the visualization came to Nurasyl after seeing similar maps created for other parts of the world. Countries such as the U.S., the U.K. and members of the European Union have overview maps and infographics, sometimes in hex-map or circle-grid formats, that present territorial data in a compact, visually appealing way.

Nurasyl wanted to bring that same approach to Central Asia, particularly Kazakhstan, where such visual maps are rare online. He recognized that data visualization could offer a beautiful and accessible way to present geographic, historical and cultural information.

While some online users pointed out minor errors in early versions of the map, such as translating Saryagash as «yellow spring» instead of the more accurate «yellow tree,» Nurasyl’s work is far from an amateur effort.

He consulted multiple sources for his translations, including Kazakh-language encyclopedias, historical maps and modern linguistic research. In some cases, he based interpretations on root word meanings (as with Aktobe and Zhanaozen), while also considering folk and historical versions of place names.