Every morning, Almaty wakes to the dull hum of traffic jams. The air — thick, dusty and heavy — seems to warn: too many cars, too little city.

In recent years, Kazakhstan’s largest metropolis has increasingly resembled Los Angeles, a city where not having a car can feel like being cut off from society. But can Almaty choose a different path, a more European one, where urban life is measured not by traffic jams, but by livability?

Kursiv LifeStyle spoke with three experts who view transportation not just as a means of getting from point A to point B, but as a mirror reflecting deeper societal choices.

The city shouldn’t have just one center

Vladislav Filatov, an architect and member of Almaty’s urban development council, pinpoints the root issue: the city isn’t choking from a lack of roads but from flawed development logic.

«Almaty is spreading,» he said. «New neighborhoods are popping up quickly, but without proper infrastructure. People move in, but there are no schools, no jobs and no nearby public transit. Everything is concentrated downtown, and everyone is going there. That puts significant strain on the transportation system.»

Filatov believes that if Almaty developed multiple centers with housing, jobs and schools, the need for long daily commutes would naturally disappear.

«Architects have proposed solutions for years, but implementation often stalls,» he noted. «Because decision-makers still think like drivers. It’s car-centric logic — designing the city around vehicles instead of people.»

According to Filatov, a dense, interconnected street grid is essential. Disconnected neighborhoods separated by empty spaces create chaos and undermine the city’s efficiency.

Driving shouldn’t be the most profitable option

Urbanist and transport analyst Adina Onalbayeva says the first step in solving Almaty’s traffic crisis is shifting public mindset.

«Myths are the first obstacle,» she said. «Like the belief that cyclists aren’t real road users. That’s simply false. A bicycle is a legitimate mode of transport, just like a car. Cyclists aren’t required to ride only on sidewalks. We have the right to use the right edge of the road.»

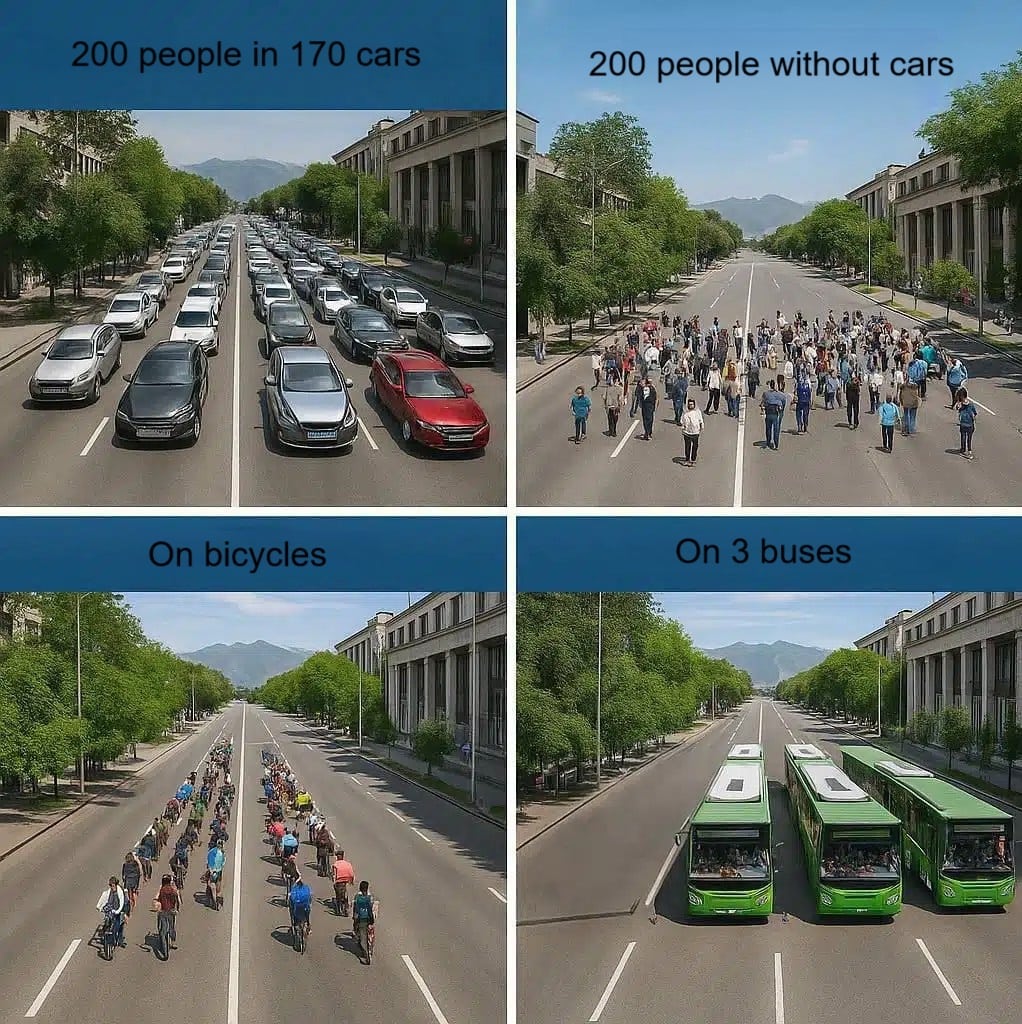

She also challenges the idea that convenience should always trump environmental concerns. People often don’t realize how much pollution their cars create. That’s where public education becomes essential — through visual campaigns, videos and posters to communicate real emissions data in a way people can easily understand.

And while reducing public transportation fares can help, Onalbayeva says that’s only part of the equation.

«A car offers comfort: space, music and air conditioning,» she admitted. «Therefore, to encourage people to choose buses or the metro, public transit must offer its kind of comfort: clean vehicles, reliable air conditioning and easy transfers. It’s not just about affordability — it’s about dignity and convenience.»

The analyst outlines three quick but often unpopular measures that could make a significant difference:

- Host regular bike events and beginner training sessions.

- Remove parking in key city areas and restrict vehicle access.

- Introduce low-emission zones and charge a fee for entering downtown Almaty.

«If we don’t make driving inconvenient, we won’t see fewer cars on the streets,» she said. «Look at London — the Congestion Charge (a fee for entering downtown in a vehicle) works. Why not apply something similar here?»

Currently, Onalbayeva says, an important project is underway: the Almaty Air Initiative, which includes plans to implement low-emission zones. It could mark a turning point in the city’s environmental and transportation policy.

«Almaty Air Initiative is a chance to show the city is ready to shift toward a more sustainable, people-focused transportation model,» she noted. «What matters most is sustaining momentum beyond the initial step.»

The value of life isn’t yet a priority

Sociologist and urbanist Alesya Nugayeva has been studying road safety for several years as part of the Vision Zero program. Her work goes beyond accident statistics to explore the underlying causes of traffic fatalities.

«We’ve held workshops, interviews and talked with experts and everyday residents,» she said. «When asked why the roads are unsafe, the most common answer is: safety just isn’t a priority. With survival as their primary concern, many people simply can’t prioritize what is perceived as a ‘luxury.’»

Nugayeva points to a critical issue in policy-making: the top-down approach. When the government enacts new traffic rules without explaining the reasons behind them, resistance follows.

«If people understood that reducing speed saves lives, their reaction would be completely different,» she said. «But we lack a culture of explanation, and without it, there’s no trust.»

Nugayeva’s research also reveals a broader imbalance in Almaty’s transportation network:

- Some routes are overcrowded, while others remain underused.

- Public buses get stuck in the same traffic as private vehicles due to limited dedicated lanes.

- Police enforcement often remains superficial, with little focus on analyzing the root causes of accidents.

Now, Alesya and her team are preparing a pilot project aimed at transforming one Almaty district, not just physically, but socially. The goal is to work hand-in-hand with residents to make real changes, from infrastructure to public engagement.

«Our goal isn’t just to rebuild a street,» she stressed. «We want to understand how to transform the environment through the community itself. When people feel ownership of their street and their city, that’s when the rules start to work.»

Media as a catalyst for change

Sustainable cities can’t exist without strong public awareness campaigns. All three experts agree on one thing: if the media wants to drive real change, it must spotlight the everyday people choosing sustainable transportation, not just the policies or infrastructure behind it.

These stories should be viewed as acts of commitment, not inconveniences.

Take student Aizhan Bolat, for example. She takes the bus every day to Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, making transfers, dealing with delays. Sometimes, her commute takes nearly an hour. She refuses to buy a car on principle.

«Yes, it’s inconvenient,» she said. «But I want to live in a city where streets are for people, not cars. I don’t want to sit alone in traffic when I could be part of the city.»

So far, decisions like hers are often seen as unusual. For many young people in Kazakhstan, a car is still a status symbol. Even when it’s not needed, owning a car is still seen as a marker of success. That cultural mindset, experts say, also needs to evolve.

All three experts note: Almaty cannot become a sustainable city without rethinking its priorities. A new district, a new development or a redesigned transit route can each be a step toward a city built for living, not just for moving.

Almaty can be different. It can be a city where streets are more than corridors for cars — they are spaces to walk, to gather and to live; where the air is clean, not thick with exhaust; where taking the bus is a deliberate, comfortable choice, not a last resort; and where no one is just a passenger, but a citizen, shaping the community with every step.