The West has the Bible and Shakespeare. Where English and Kazakh sayings diverge?

World Folklore Day, observed annually on Aug. 22, celebrates oral traditions and communal practices — a body of expressive culture that forms the foundation of societies. It marks the anniversary of the 1846 publication in London of an article by British scholar William Thoms in The Athenaeum magazine, in which he used the word «folklore» for the first time.

Among folklore’s most enduring expressions are proverbs and idioms — short, memorable phrases that condense generations of experience, values and social norms into the distilled wisdom of a nation.

Based on personal experience and observation, I have explored the distinctive features of Kazakh proverbs and sayings, and compared them with their English and Russian counterparts.

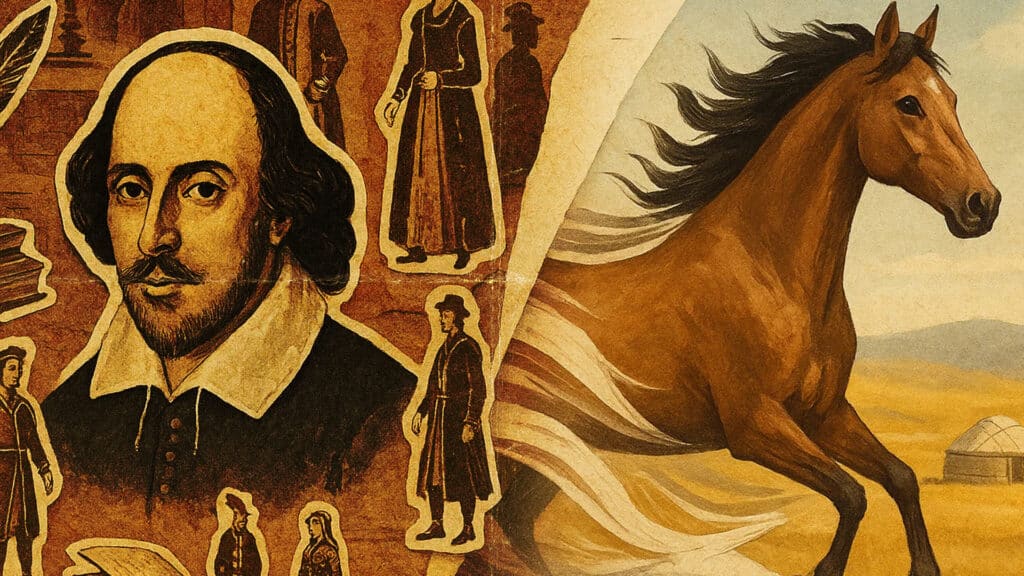

Bible and Shakespeare

About 10 years ago, a colleague and I were taking an interpreting course. One day, he brought his young daughter to class. She sat quietly at a desk in the back, watching us practice. The trainer would say a short fragment — two or three words, a phrase — in Russian, and we had three seconds to produce the correct equivalent in English.

From morning to afternoon, we worked through large blocks of vocabulary, «pumping» them into memory. Between exercises, we reviewed errors, heard the teacher’s commentary, and listened to examples and stories from translation practice.

At the end of one class, my colleague introduced his daughter to the trainer and asked whether she had enjoyed it. She said she had, but wondered why so many examples came from the Bible.

At the time, I didn’t think much of her question and hadn’t noticed the abundance of biblical references. But over time, I realized she was absolutely right. The evidence can be found in countless specialized collections — such as John Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations — as well as in dictionaries and translation textbooks.

A significant number of well-known and long-established proverbs and idiomatic expressions in English can be traced to the Bible and the works of Shakespeare.

Other rich sources of set expressions exist as well — mythologisms form another sizable category, such as Achilles’ heel and labor of Sisyphus.

In terms of sheer number, however, biblicalisms — such as Man shall not live by bread alone, A fly in the ointment, and Whoever is not with me is against me — and Shakespeareisms — such as All that glisters is not gold, To be or not to be: that is the question, and Wear one’s heart upon one’s sleeve — likely top the list.

‘When pigs fly’ in Kazakh

Out of professional habit, when reading Russian or English dictionaries that collect common expressions, idioms and proverbs, I often look for the Kazakh equivalents, Kazakh being my native language.

In some cases, I prefer the equivalent in one language over its counterpart in another, either because it is easier to remember or because it evokes more pleasant associations.

But there are also examples — remarkable in their imagery, different in form yet unified in meaning — that are memorable in all three languages. In my view, the key is to literally picture what is being said:

- English: When hell freezes over; when pigs fly.

- Russian: Kogda rak na gore svistnet [lit. when the crayfish whistles on the mountain]; posle dozhdichka v chetverg [after a little rain on Thursday].

- Kazakh: Tezek güldegende [when the dung or manure blooms]; eşkınıñ qūiryğy aspanğa jetkende [when the goat’s tail touches the sky].

- English: Make a mountain out of a molehill.

- Russian: Delat’ iz muhi slona [making an elephant out of a fly].

- Kazakh: Tüimedeidı tüiedei etu [make a camel out of a button].

This raised a question: What might we discover if Kazakh idioms were classified by origin, source and other characteristics?

From the examples I gathered at the time — without an in-depth review of the literature — I gained the impression that themes involving livestock and wild animals are especially well developed in the Kazakh language. This includes comparing people to animals, citing animal habits and behaviors, and noting breeding practices for specific species.

- English: Evil communications corrupt good manners.

- Kazakh: Aram maldyñ arty azap [filthy cattle: you can’t get rid of problems].

- English: No fool like an old fool.

- Kazakh: Atan tüie oinaqtasa, jūt bolar [there will be trouble if a castrated camel frolics].

- English: No garden is without its weeds

- Kazakh: Bır bieden ala da tuady, qūla da tuady [one mare will give birth to both a piebald foal and a dun foal].

I decided to test this assumption by reviewing the available literature, including Russian-Kazakh and English-Kazakh phraseological dictionaries.

Zoomorphisms and dairy products

My initial impression was confirmed: the largest number of sayings in Kazakh relate to domestic and wild animals, so-called zoomorphisms.

Zoomorphisms exist in both English and Russian. In this case, however, the focus is on familiar, commonly used Russian or English sayings that, in their Kazakh equivalents, feature the names of animals.

This category of Kazakh idioms is particularly vivid:

- Not to show up (show one’s face) – At ızın salmau [a horse won’t set foot].

- In the middle of nowhere – İt ölgen jerde [where the dog died].

- Bare as a bone – Jylan jalağandai [like a snake licked].

- Like two peas in a pod – Egız qozydai [like twin lambs].

- Much ado about nothing (storm in a teacup) – Aidağany ekı eşkı, ysqyryğy jer jarady [he drives only two goats, and the noise is all over the neighborhood].

- The mills of God grind slowly, but they grind exceedingly small – Ögızge tuğan kün būzauğa da tuady [what happened to the bull will happen to the calf].

- Lavish feast – Aq tüienıñ qarny jaryldy [the white camel’s belly burst].

Second in number are dairy-related expressions — covering the preparation, storage and use of milk and fermented dairy products, as well as the names of these products:

- In perfect harmony – Süttei ūiu [to curdle like milk].

- Music to someone’s ears – Qūlağyna maidai jağu [be as sweet as butter].

- Shame (disgrace) oneself – Abyroiy airandai tögıldı [to lose your reputation like spilled airan].

- True angel – Sütten aq, sudan taza [whiter than milk, clearer than water].

- In pristine condition – Qaimağy būzylmağan küide [like fresh, unspoiled sour cream].

Two other major categories of Kazakh idioms are those that reference celestial objects — such as the sun, moon and stars — and those about family and kinship, including parent-child ties, traditional hierarchies, and relationships among close and distant relatives:

- As clear as day – Aidai anyq [as clear as the moon].

- Someone’s luck held – Aidan ızdegenı aldynan tabyldy [he found what he was looking for on the moon right under his nose].

- Smiles of fortune – Jūldyzy oñynan tudy [his star has risen on the right].

- Cut from the same cloth (birds of a feather) – Ağama jeñgem sai, apama jezdem sai [my sister-in-law is just like my older brother, my sister is just like my brother-in-law].

- What am I – chopped liver? – Bız ne, toqaldan tudyq pa? [what are we, born of a younger wife?].

- Be beside oneself with joy – Äielı ūl tapqandai quanu [to rejoice as if his wife had given birth to a son].

The nomadic way of life and pastoral animal husbandry shaped how our ancestors saw the world. Some of the sayings mentioned above remain in use, while others are fading, yet the language — and our collective mindset — would be unimaginable without them.