Despite the deficit of top-class warehouses in Kazakhstan, professional warehouse developers aren’t keen to invest in new projects. They prefer building warehouses for big lessees. There is a small circle of clients, so such warehouses are rarely seen in the broader market. As a result, retailers have to invest in building warehouses on their own.

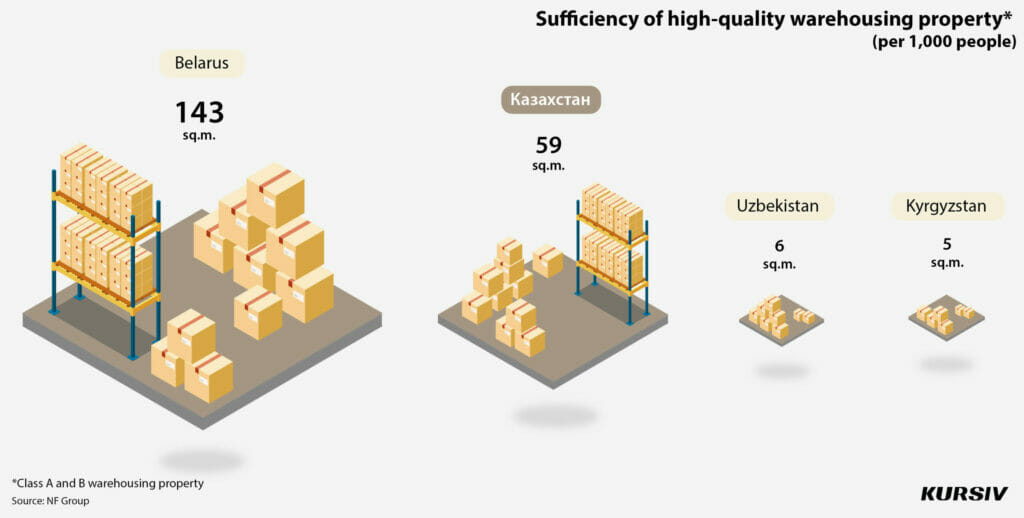

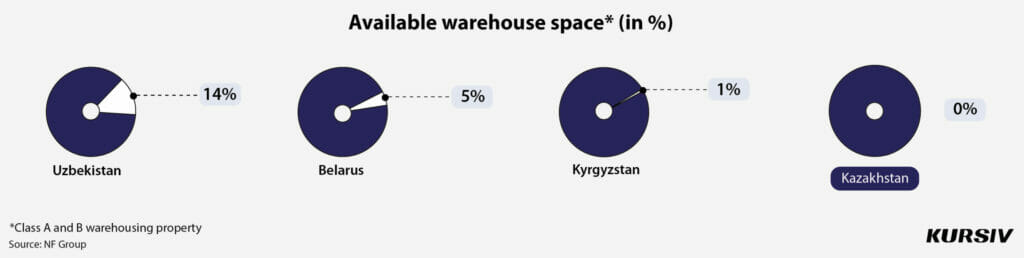

The current amount of warehousing property in Kazakhstan is about 1.13 million square meters (59 square meters per 1,000 people). This rate is half as much as in Belarus but ten times higher than in Uzbekistan or Kyrgyzstan. At the same time, there is zero available space in top Class A and Class B warehouses in the country, according to NF Group (former Knight Frank Russia).

Even though the demand for high-quality warehousing properties is very high, the speed at which new warehouses are entering the market is relatively modest and the competition between market actors is low, analysts say. The Kursiv edition has approached the market actors with the request to comment on this situation.

A warehouse with amenities

According to METRO, which specializes in product supply to HoReCa, every type of product has specific requirements for storage. In order to keep food fresh and high quality, a warehouse must maintain the right temperature and lighting. Moreover, some food products must be stored separately.

For example, noodle products and sugar don’t like sunlight, while herbs and dehydrated mushrooms cannot be stored near dairy or eggs, which absorb the smell easily.

Medicine, electronics and home appliances also require separate storage space and control of climate. Many of these products don’t like moisture, rapid changes in temperature or heat from the heating system, for example. In other words, these products must be stored at Class A and Class B warehouses. Unlike Class C warehouses, they are equipped with fridges, heating units and off-grid electric substations.

Professional grade logistics and warehousing are absolutely necessary for retailers to maintain good shape and quality of products and to stay competitive in the market. «Consumers won’t wait for you to bring a product if someone else can make the same offer. You will lose sales and consumer loyalty if you have no product on your shelves. Moreover, poor logistics can affect the prime cost of a product,» said one of Kazakhstan’s developers.

Expensive money

The past three years (2020-2022) were quite turbulent, although pharmaceutical and FMCG companies, home appliances, electronics and fashion retailers – the key clients to the top-class warehouses – reported virtually no losses. In fact, pharmaceutical companies increased their import of drugs from $1 billion before COVID-19 to $1.6 billion amidst the pandemic. In 2021, home appliances and electronics retailers reported a 38% growth over the previous year. This growth was still happening in 2022, although it was less impressive. Physically, retail trade grew by 6.5% in 2021 and 2.1% in 2022.

As these businesses and warehouse properties are in hand-to-glove cooperation, Class A warehouses were already 90% occupied in 2019. In 2020-2021 the demand for this type of property reached 100%.

«There is no available space in Class A and Class B warehouses in Kazakhstan. On the one hand, this means that the demand for high-quality warehousing property is extremely high. On the other hand, we know that the construction of new warehouses isn’t massive,» NF Group said in October 2022.

Even though this industry has incredible potential for future growth, high levels of interest rates prevent it from further developing, experts say.

«It is almost impossible to implement any big project in Kazakhstan when interest rates are about 20-25% per annum,» according to Eugene Dolbilin, partner of Scott Holland | CBRE in Central Asia and Kazakhstan. «You have to put about $1,000 per one square meter of a warehouse on average. The rent payment is about $7,000 to $12,000 per month or $90,000 to $130,000 a year (roughly 10%). At the same time, you must return about $200-240 out of every $1000 of profit to the bank. No business is going to work this way,» he added.

Provide oneself

Given the reality of the Kazakhstani warehousing market, developers prefer to implement built-to-suit projects when they build a warehouse for a certain customer, according to NF Group. As a result, two-thirds of warehousing property in the country is already occupied when it enters into operation. In other words, these new warehouses do not add any additional storage space for the broader market, NF Group noted.

Big retailers like this method because they can obtain a warehouse designed for their specific needs, while warehousing property owners get a cash flow without looking for clients in the open market.

However, those retailers who have recently come to Kazakhstan face shortages of top-class warehousing property and are often forced to build such property on their own.

«In Kazakhstan, only 32% of Class A warehousing property is available for lessees, which is not enough for a proper choice. Given that almost all top-class warehouses in the country are already occupied, for some companies, it might be reasonable to build a warehouse on their own,» said Konstantin Fomichenko, regional director of the industrial and warehousing property department in NF Group.

When METRO came to Kazakhstan in 2008, it struggled to find a reliable partner who could help the company with warehouse logistics. After 15 years, the company runs 56,000 square meters of Class A and Class A+ warehouses in seven towns throughout the country and leases warehouses in six other locations.

These days the situation is mostly the same. In 2022, several foreign retailers said they would develop logistic infrastructure on their own as they need more storage space.

Wildberries is one such retailer planning to build a big logistic center and looking for a proper location.

The Russian online marketplace has been developing its logistical infrastructure both on its own and in conjunction with local entrepreneurs. The company has already run two hubs in Almaty and Astana. In Q3 2022, it opened a new drop-off center in Korgas. «In 2023, we will continue to build and lease out new warehousing property,“ Wildberries said.

Another Russian marketplace, Ozon, leases out two distribution facilities in Almaty and Astana. It will also open a fulfillment center to store products from local merchants and form online orders.

In December 2022, Turkish retailer LC Waikiki opened its second-largest store outside Turkey in Almaty. During the opening ceremony, the company’s representatives confirmed that LC Waikiki would invest $15 million into a new logistical center in Almaty. The warehouse of 20,000 square meters is expected to be opened in 2023.

Several other foreign retailers are also interested in developing logistical potential in Kazakhstan, although they declined to reveal any details, citing the high level of competition in the market.

Dead end or promising outlook?

The vast majority of experts agree that retailers are simply forced to step into the warehousing business and build storing properties on their own because of the necessity to remodel logistical chains between Asia and Europe. However, they disagree about Kazakhstan’s role in big retailers’ plans.

“Kazakhstan has a very good geographical location that allows the country to pose as a large consumer market between Eastern Asia and Europe. On the other hand, the purchasing power of Kazakhstanis makes the country an attractive place for retailers,» NF Group said.

«Ozon has been interested in CIS member states for years. The company wants local merchants to be represented on the marketplace,» according to Molder Rysaliyeva, director general of Ozon Kazakhstan.

«Taking into account the geographical location of Kazakhstan and its market potential, I can say that this country plays a strategically important role for our brand. We supply all other Central Asian countries from here,» said Ilker Hacioglu, deputy head of international retail in LC Waikiki.

Eugene Dolbilin is less optimistic.

«It is unnatural when retailers have to raise funds and build warehouses in Kazakhstan on their own. First, professional development means that professional logistical companies build the infrastructure while professional funds finance such projects. Second, Kazakhstan isn’t attractive to many international retailers. This is a vast country with a small and dispersed population. People here have quite low incomes, while logistical costs are high. Moreover, we have very expensive lending. The current trend is a result of sanctions against Russia. Retailers have to adjust themselves to the situation. They are implementing logistical projects in Kazakhstan because they keep the entire Central Asian region in mind. Kazakhstan is just a transit point that attracted their attention because of the current geopolitical situation,» the partner of Scott Holland | CBRE in Central Asia and Kazakhstan highlighted.