Forget Steve Jobs, meet Abai: The unlikely guru for Kazakhstan’s entrepreneurs

In today’s business culture, outcomes such as financial success or market dominance often overshadow how they are achieved, even when those means involve aggressive tactics or ethical compromises.

A contrasting perspective, however, emphasizes the integrity of intentions behind actions. As the great 19th-century Kazakh poet and philosopher Abai wrote in his Book of Words, «Judge a man’s qualities by the intentions of his action and not by its outcome.»

As Kazakhstan marks the 180th anniversary of Abai’s birth this year, his philosophy remains strikingly relevant — even in fields where one might not expect it, such as entrepreneurial research and education.

Holistic human beings

A recent example highlighted on social media by Shumaila Yousafzai, a professor at the Nazarbayev University (NU) Graduate School of Business in Astana, demonstrates how indigenous knowledge can be a powerful tool for shaping modern approaches to sustainability, entrepreneurship and governance.

Last year, Professor Yousafzai submitted three grant proposals for potential funding through NU’s internal research grant system and Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Science and Higher Education. Each proposal focused on a distinct group: women entrepreneurs, entrepreneurs with disabilities and grassroots business trainers.

This time, however, she took a different approach — grounding each project in the philosophy of Abai Kunanbaiuly, Kazakhstan’s most revered poet and thinker.

Each proposal draws directly from Abai’s Book of Words and his concept of Tolyk Adam, the idea of a «complete» or holistic human being, guided by the harmony of heart, mind and will. Yousafzai argues that this framework is deeply relevant to today’s global challenges, including ethical business practices, environmental sustainability and social inclusion.

She built her case around the belief that individuals with physical disabilities already possess everything needed to become complete human beings through moral, intellectual and emotional development. And that women entrepreneurs can be empowered not solely through imported development models, but by drawing on indigenous wisdom rooted in their cultural heritage.

Relevance of Western theories

Many discouraged Professor Yousafzai from pursuing her unconventional approach. «These grants are evaluated in the West,» some warned, referencing the peer-review process used for project selection. «No one knows who Abai is.» Others called it too risky to use an indigenous framework.

Today, the researcher is proud to report that all three proposals were awarded funding, totaling more than $500,000. And every activity within those projects is rooted in Abai’s poetry, his wisdom and his enduring philosophy.

The decision to ground the projects in Abai’s thought was not only intentional but deeply personal, Yousafzai explains. Over the years, she says, she has grown disillusioned with the forced application of Western theories to contexts they were never meant to explain. While these frameworks have their merits, she argues, they are far from universal.

«The Global South — diverse, complex, wounded and wise — deserves tools that emerge from its soil,» Yousafzai said. «When we continue applying theoretical models rooted in histories of colonization, extractivism or market fundamentalism, we often do more than misdiagnose — we perpetuate harm.»

In contrast, indigenous knowledge, too often dismissed as mere folklore or tradition, is a sophisticated and nuanced system for understanding the world. It speaks directly to local realities, values and aspirations. Reconnecting with this wisdom is not about romanticizing the past, the researcher emphasizes. Rather, it’s about recognizing that many of the answers we seek have already been offered — by poets and philosophers, by farmers and elders, by spiritual leaders and communities.

According to Yousafzai, engaging with indigenous philosophies like Abai’s is not an act of nostalgia. It is an act of epistemic justice, a deliberate choice to prioritize relevance over replication.

Abai is more than a cultural icon

Professor Yousafzai and her team at the NU’s Research Centre for Entrepreneurship have developed training modules and delivered them across multiple regions of Kazakhstan, including Astana, Almaty, Semey and Aktobe. Each training curriculum follows a three-stage structure inspired by Abai’s philosophy of the Tolyk Adam: it begins with exercises encouraging participants to reflect on their intentions (heart), followed by sessions on strategy and decision-making (mind) and concludes with guidance on action and perseverance (will).

These stages are integrated with core environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles, demonstrating that Abai’s wisdom can meaningfully shape how one builds and runs a business — ethically, responsibly and sustainably.

Initially, participants often arrive skeptical. While they respect Abai as a national and cultural icon, many struggle to see how his ideas relate to profit, branding or finance. But by the end of the training, the narrative shifts. Participants frequently share how moved they are to reconnect with Abai, not just as a poet or philosopher, but as a source of moral and intellectual guidance in everyday life, including business.

Professor Yousafzai and her team believe their message is clear — especially for scholars across the Global South: stop relying on theories never meant for your context, and start trusting the wisdom that already lives in your language, your land and your people.

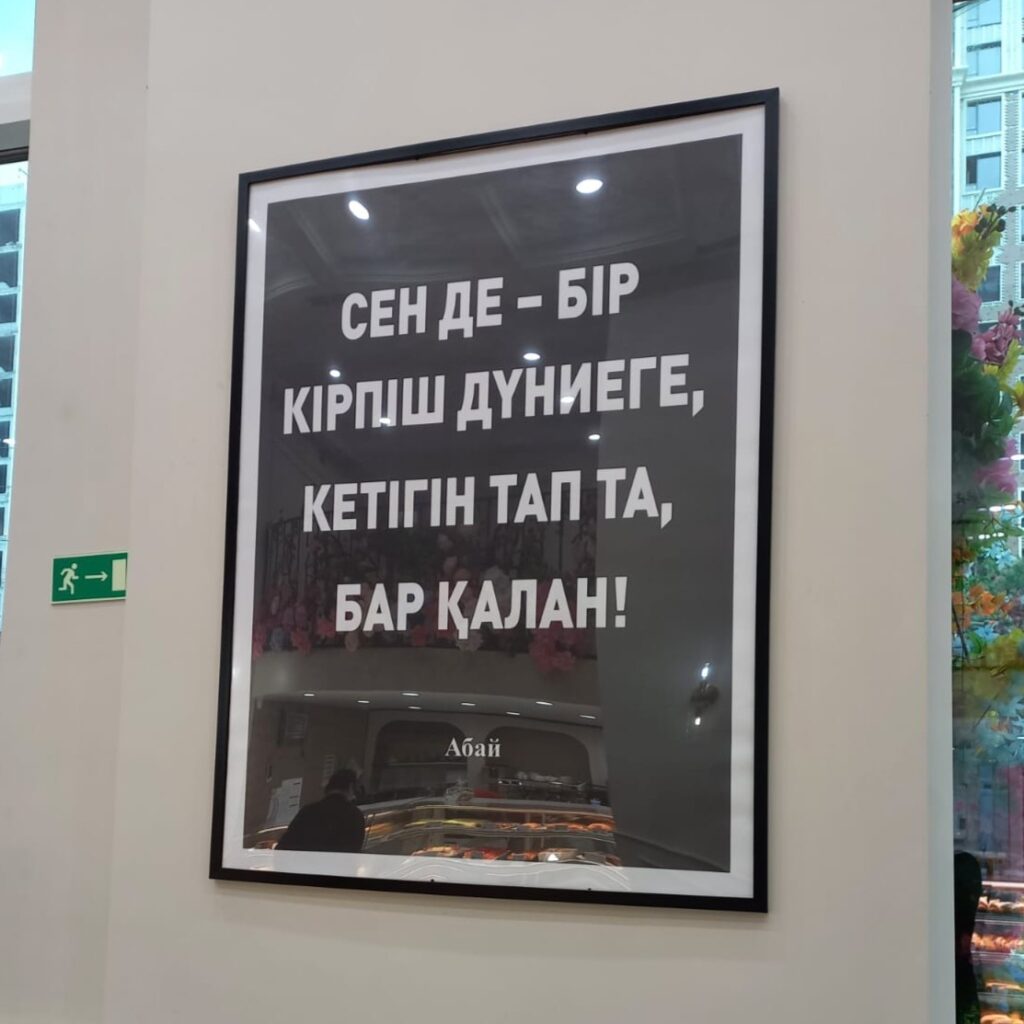

Admittedly, maintaining integrity in business brings only benefits — and as Abai advises in his 43rd word of wisdom, one should practice moderation in all things:

«There is a measure to everything on earth, the good things of life included. It is a great blessing to have a sense of measure. […] One ought to show the right measure in eating, drinking, amusing one’s self and getting rich, in seeking power and even in practising caution and vigilance in order not to be tricked. All that is excessive is evil.»