A newly released video tour of Russian restaurateur Alexander Orlov’s apartment in Tashkent impressed viewers with its lavish décor and traditional furnishings. The film crew’s biggest surprise was the restaurateur’s «family heirloom» — a walrus penis, described as a decorative curiosity.

Fossilized artifact

The object, a white bone with intricate carvings, surprised the presenter, who identified it as a fossilized walrus organ. Orlov explained its bone-like nature stems from walruses’ cold habitats — otherwise, “they would freeze and lose vitality.”

This unusual discovery naturally raises an intriguing question: why do people collect human or animal genitals?

Unusual collections

People collect, and museums display, human and animal genitals or objects symbolic of them for several overlapping reasons, including:

- Scientific curiosity (anatomy, comparative biology).

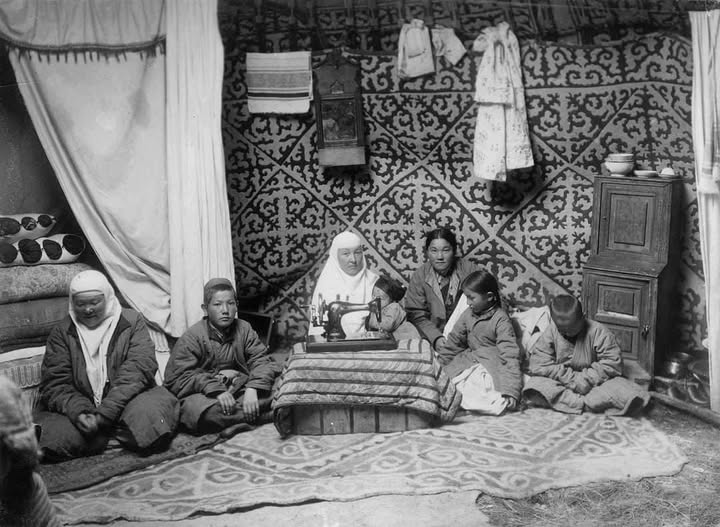

- Historical and anthropological interest (amulets, fertility rites).

- Social activism (destigmatizing anatomy).

- Simple human taste for the unusual or taboo.

Collections may begin as private hobbies and later become research or educational resources that encourage discussion and serve as objects of material culture that help in the production of sexual knowledge.

No shame in what is natural

Science and natural history drive some collections. The Icelandic Phallological Museum began as a private study of mammal penises and now houses hundreds of specimens used to illustrate species differences and reproductive biology.

Located in Reykjavík, the institution houses the world’s largest collection of penises and penile parts, enabling individuals to undertake serious study of phallology in an organized and scientific manner.

Historical context and ritual practices motivate other collections. For example, phallic amulets in ancient Rome (the fascinus) held protective and religious significance. Museums and academic collections display these artifacts to trace beliefs about fertility, protection against evil, and symbolic power. The phallus was considered a token of the state’s protection and stability. It was venerated as a symbol of masculine generative power, traditionally associated with the hearth and viewed as sacred.

Public health and activism

Public health and activism have given rise to new institutions, such as the Vagina Museum in London, which utilizes models, replicas, and exhibits to educate, combat stigma, and provide accessible anatomical knowledge — shifting genital objects from private curiosity into civic pedagogy.

Together, these sites show that such collections lie at the intersection of science, history, ritual, and social change — inviting visitors to confront taboos while learning tangible facts.