Leading the field in nominations does not ensure a Nobel Peace Prize win. As our previous review of the Norwegian Nobel Committee archives for 1974 showed, Andrei Sakharov was among the most frequently nominated candidates that year — yet he did not receive the award. He would go on to win in 1975.

Read also: Four days left to nominate the next Nobel Peace Prize winner.

In 1975, the committee received 121 nominations. Sakharov led all individual nominees with 13 nominations. However, the overall front-runners were two international youth organizations: the World Organization of the Scout Movement, based in Switzerland, and the World Association of Girl Guides and Girl Scouts, based in the United Kingdom. Each received 25 nominations.

Strong backing for global youth movements

The two Scout organizations, global counterparts focused on youth education and civic responsibility, were nominated by a wide range of international figures, including George G. Thomson, Errol Barrow, Sirimavo Bandaranaike, Alec Douglas-Home, Hubert Humphrey and Eisaku Sato, among others.

In his nomination letter, Sato — a former Japanese prime minister and 1974 Nobel Peace Prize laureate — praised the organizations for their «contributions to the cause of international understanding, friendship and peace.» He highlighted their role in education outside the classroom in Japan and noted his personal connection to the movement.

«With great pride I recall that it was during my tenure as prime minister that the Boy Scouts of Nippon honored me with its highest award, the Order of the Golden Pheasant,» he wrote.

Similarly, Dutch parliamentarian Henry J. B. Aarts commended the two movements for more than six decades of work promoting «universal peace and understanding» through youth education worldwide.

Other leading organizational nominee

Another prominent organizational candidate in 1975 was the Inclusion International, then known as the International League of Associations for the Mentally Handicapped. The group received 11 nominations from figures including Maurice Schumann, five members of Israel’s parliament, several Belgian lawmakers and Gerhard Jahn.

Thomas Desmond Williams, professor of modern history and dean of arts at University College Dublin, described the league’s work as philanthropic and international in scope. He wrote that by advocating for people with intellectual disabilities and promoting their full participation in society, the organization fostered broader understanding across racial, social and religious lines — a mission directly tied to the cause of peace.

Most nominated individuals in 1975

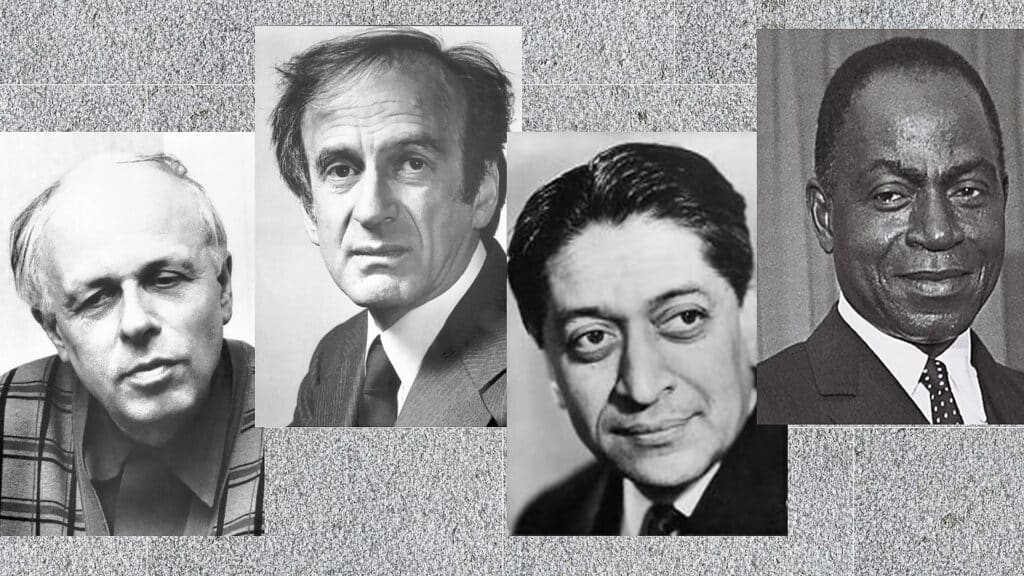

Based on archival materials, the individuals who received the most nominations in 1975 were:

- Andrei Sakharov (Soviet Union) — 13 nominations.

- Elie Wiesel (Romania) — 8 nominations.

- Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Ivory Coast) — 7 nominations.

- Romesh Chandra (India) — 6 nominations.

Félix Houphouët-Boigny, Ivory Coast’s first president, promoted regional stability and dialogue in West Africa. He helped found the Conseil de l’Entente and later inspired the creation of a UNESCO peace prize bearing his name. His nominators included senior officials from Ivory Coast, Italy and France.

Romesh Chandra, president of the World Peace Council, was an outspoken anti-war activist and frequent speaker at the United Nations who opposed military alliances such as NATO. His supporters included lawmakers from India, Israel, Germany, Finland and Cyprus.

Countries most active in nominations

Archival records show that the most active nominating countries in 1975 were:

- U.S.: Frequently nominated individuals such as Elie Wiesel, Norman Cousins and Andrei Sakharov, as well as the Scout movement.

- France: Actively supported Félix Houphouët-Boigny and Inclusion International.

- Germany: Often nominated Sakharov and Romesh Chandra.

- Sweden and Norway: Parliamentary representatives backed Sakharov and several international organizations.

- Israel: Nominated candidates including Sakharov and Chandra.

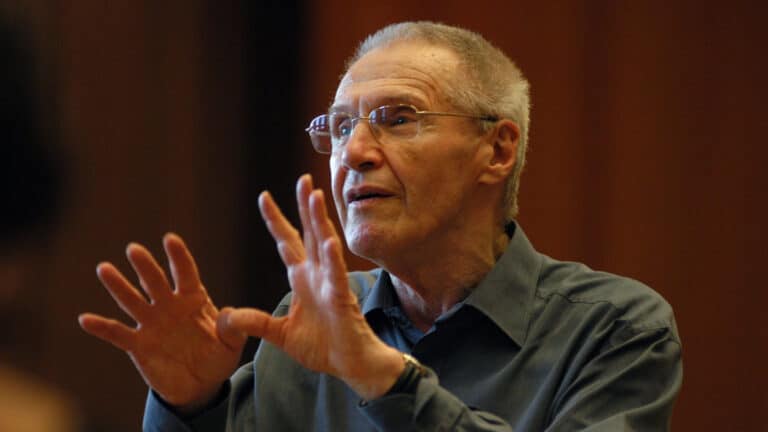

The winner: Andrei Sakharov

Sakharov, often described as the father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975 for his opposition to abuses of power and his defense of human rights.

In a joint statement, Israeli academics and members of the Knesset — including Avraham Harman, Gabriel Warburg, Menachem Begin and Shulamit Aloni — praised Sakharov’s «exceptional qualities of courage and perseverance» and noted the personal risks he accepted in defending human rights.

In a letter to the Nobel Committee, U.S. Sen. Henry M. Jackson described Sakharov as an «internationally respected scientist and humanist» whose influence rested on «the persuasiveness of his principles» rather than political power.

«With great eloquence and insight he has maintained that a reconciliation between East and West must begin with a genuine détente, one which reflects progress in the area of human rights. No one has articulated more compellingly the need for a lowering of the artificial barriers which stand between peoples,» Jackson wrote.

Soviet leaders reacted angrily and refused to allow Sakharov to travel to Oslo to accept the award. His wife, Yelena Bonner, accepted the prize on his behalf. Sakharov was stripped of his Soviet honors, and the couple was kept under strict surveillance in the city of Gorky for several years. Only after Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985 were they permitted to return to Moscow.

Editorial note:

Under the rules of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, access to its Nomination Archive may be granted only after 50 years have passed from the date of the relevant decision.

In early January 2026, a member of Kursiv.media’s editorial team was granted access by the Norwegian Nobel Institute to archival materials related to the 1974 and 1975 nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize.

The archival materials cited in the publication are used courtesy of the Norwegian Nobel Committee Archives, the Norwegian Nobel Institute, Oslo. We thank the Committee and the Institute for granting access to the records.